What are the most effective messages to increase climate action

Our latest research evaluates into the best messages to bolster support for climate action and how we planted over 300,000 trees (plus we share a number of new papers and pre-prints)

The climate crisis is one of humanity’s most pressing threats to existence. Without change at both the systemic and individual level, humans risk a future of rising seas, forest fires, and heat waves But how can behavioral scientists and policymakers change people’s beliefs and actions around climate change?

In our latest paper led by Madalina Vlasceanu, Kim Doell, and Jay, we investigated the impact of several popular climate change interventions on people’s climate change beliefs, behaviors, and policy support across the globe. We decided to write a summary of the main findings in this newsletter. Our paper was published in Science Advances this month and Madalina and Jay also wrote an op-ed in Scientific American if you want to learn more.

There has been a lot of research in the behavioral sciences studying different ways to boost green behaviors and intentions. However, many of these interventions are tested in different labs with different samples and measures, making it hard to compare their effectiveness. Thus, we compared many interventions across the same outcome variables in one large experiment, to effectively determine how each one stacks up against the other in a controlled test.

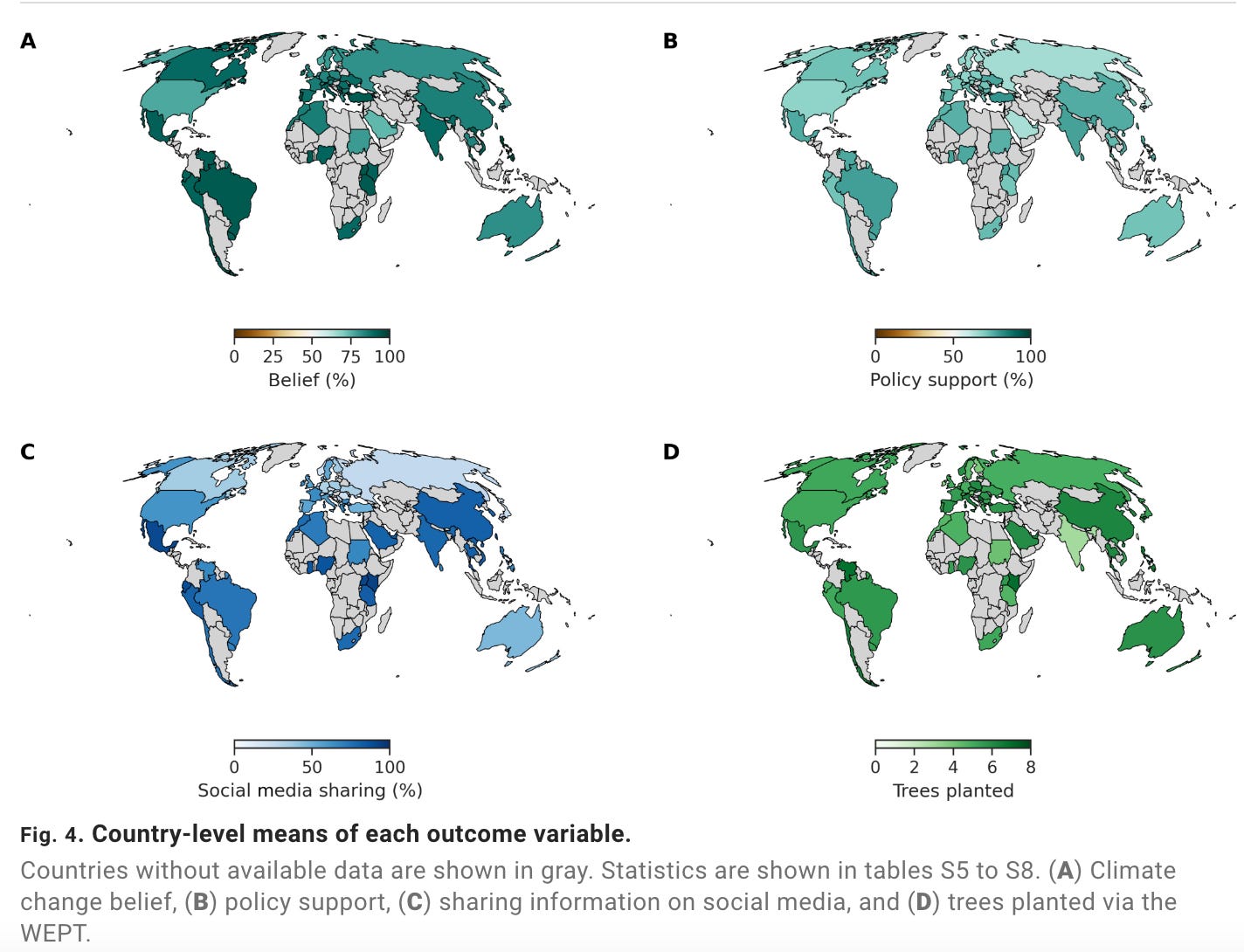

Another challenge in climate change research is that it has mainly been conducted in America as well as other Western, educated samples from industrialized, rich and developed countries (known as “WEIRD” samples). However, climate change is a global phenomenon that requires international cooperation and behavior change across a wide variety of cultures. We used the many labs approach to conduct the study in numerous labs around the world and recruit an international sample, to see how culture shapes the impact of climate change interventions. (We have a paper examining culture factors you can read here).

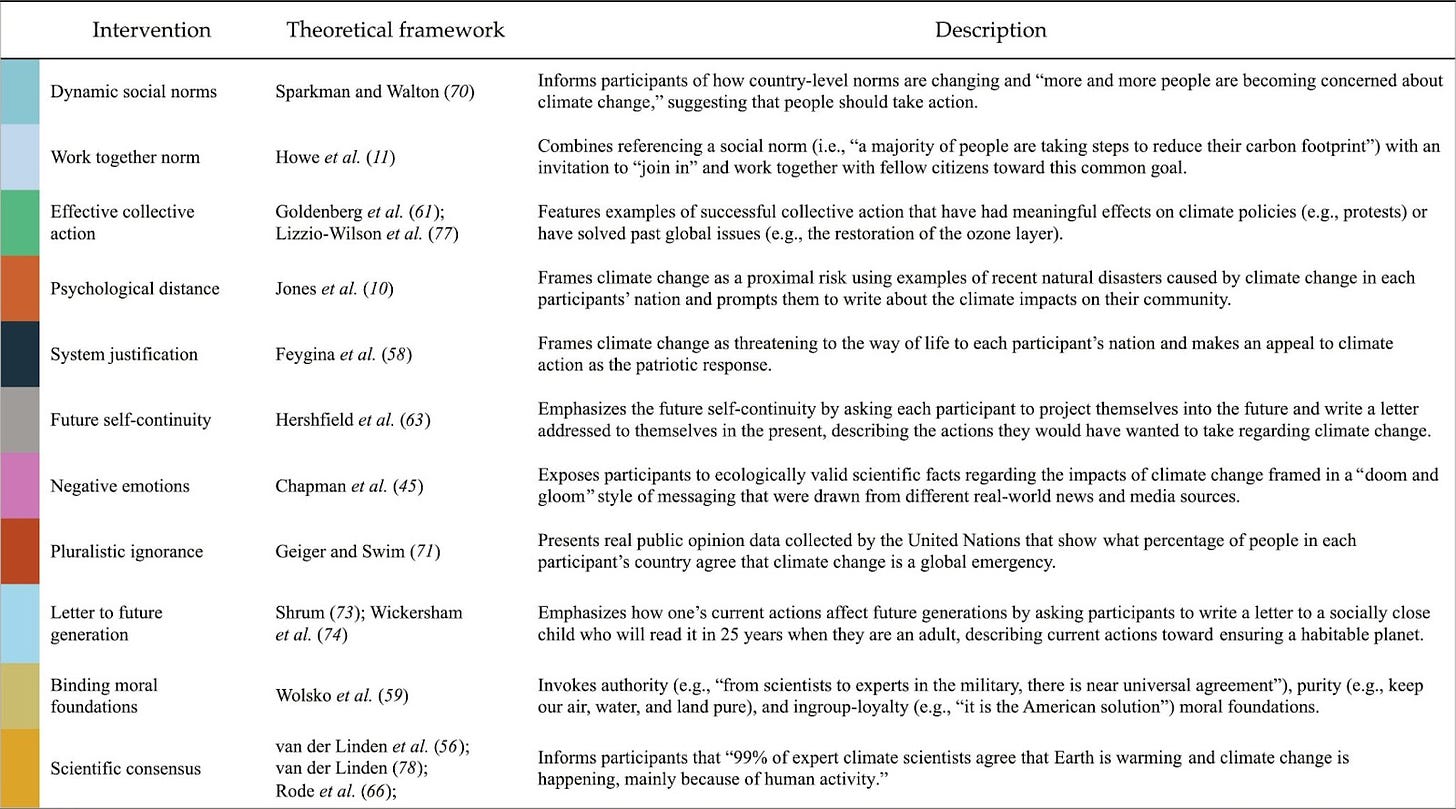

In order to determine what interventions to test, we crowdsourced interventions from numerous climate change scholars–asking experts to send us the very best interventions based on prior research. We then selected and tested the 11 most promising climate interventions in our study, each focusing on different psychological frameworks. This also allowed us to test a number of population theoretical frameworks in psychology, from Moral Foundation Theory to System Justification theory. In fact, we worked closely with the authors of these prior papers to ensure high quality interventions.

For example, some interventions focused on social norms, while others reduced the psychological distance between individuals and the consequences of climate change. Another intervention talked about the consequences of climate change using a “doom and gloom” style of messaging (see table below for a description of all the interventions). What do you think will work best?

These 11 interventions were tested by 59,440 participants in 63 countries across on four different outcome variables:

Belief in climate change (e.g., to what extent people gauged climate change statements as accurate, such as “Climate change poses a serious threat to humanity”)

Support for climate change mitigation policy (such as significantly expanding public transportation infrastructure)

Willingness to share climate change information on social media (“Did you know that removing meat and dairy for only two out of three meals per day could decrease food-related carbon emissions by 60%?”)

Willingness to contribute to pro-environmental action (in this case, tree-planting) by doing a cognitively challenging task.

Overall, we found that the different interventions had small but significant effects globally. But the impact of the interventions varied widely based on the outcomes that were targeted and different characteristics of the audience. There was no silver bullet or one intervention to rule them all.

For example, climate change beliefs were strengthened most by decreasing the psychological distance of the effects of climate change. Writing a letter to a child in the future describing the actions you were taking in the present to fight climate change was most effective at increasing support for climate mitigation policy. Social media sharing was most increased by exposing people to “doom & gloom” style messages that invoked negative emotions.

But what changed actual behavior?

Sadly, no interventions increased effortful behavior towards fighting climate change via the tree planting task. In fact, half of the interventions seemed to decrease this pro-environmental action. They backfired!

The effectiveness of the interventions also varied depending on people’s initial belief in climate change. In particular, the same “doom and gloom” style messages that most effectively increased social media sharing also decreased tree-planting action overall, and decreased policy support among those with low initial belief in climate change. This is unfortunately because tree planting was our only measure of effortful behavior.

Overall, these results prove that not all interventions are a one-size-fits all solution. Scholars need to be far more modest in their claims about these messages and practitioners need to be careful about what interventions they want to use to achieve their desired goals. This means we need better and more nuanced theorizing on this topic if we hope to develop more effective interventions. Many theories were fruitful for one, or two outcomes, but none was effective at generating an intervention that worked across the board.

As Kurt Lewin famously said, “there is nothing as practical as a good theory”. Hopefully this data will send scholars back to the lab to develop better theories and these will lead to more effective climate change messaging. This is an exciting opportunity for advancing our understanding of one of the most important topics facing humanity. We believe that behavioral science is up to the task.

However, we also found a number of promising results. Overall, the majority of participants in the study expressed belief in climate change - 86% said that they recognized the dangers presented by climate change, and over 70% supported policy action geared towards mitigating climate change! There seems to be a global consensus on the existence of climate change that needs to be translated to action and support for policy.

However, this baseline belief and the effectiveness of each climate change intervention varied depending on country, demographics, and initial beliefs. For instance, emphasizing scientific consensus on climate change increased support for climate friendly policies in Romania by 9%, but decreased support by 5% in Canada. These results have striking implications for how policymakers should tailor their messages based on their audience and target behaviors (and, again, suggest the need for more culturally sensitive theories).

As a result of participants’ behavior in the study, our team actually planted 333,333 trees with a donation to The Eden Reforestation Project!

You can watch a video summary of this project here—please share this newsletter and video with anyone you know who might find it interesting or useful.

A video abstract created about our paper by one of the paper’s co-leads, Madalina Vlasceanu.

If you are interested in seeing what interventions are most effective for a specific type of audience, we created a web tool that can easily show the effectiveness of each intervention depending on a range of factors like country, political ideology, age, gender, etc. While the sample size of each subset and the fact that the results are based on percent change compared to the control should be taken into account, it’s an easy way to see what interventions worked best for specific populations. You can use the web tool here.

If you want to learn more about the paper, you can read NYU’s press release here, and Jay & Madalina’s op-ed in Scientific American here. To read the paper itself, you can use the links in the citation below. This project was funded, in part, by grants from New York University and Google Jigsaw to our lab.

Vlasceanu*, M., Doell*, K. C., Bak Coleman*, J. B., Todorova, B., Berkebile-Weinberg, M. M., Grayson, S. J., Patel, Y., Goldwert, D., Pei, Y., Chakroff, A., Pronizius, E., van den Broek, K. L., Vlasceanu, D., Constantino, S., Morais, M. J., Schumann, P., Rathje, S., Fang, K., Aglioti, S. M., ... Van Bavel, J. J. (2024). Addressing climate change with behavioral science: A global intervention tournament in 63 countries. Science Advances, 10, eadj5778. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adj5778

News & Events

Two of our lab members were recently named Rising Stars! Steve Rathje, a current post-doc in the lab, and Billy Brady, who was a former PhD student in the lab, were both awarded the Association for Psychological Science Rising Star award! The APS Rising Star designation is presented to outstanding APS Members in the earliest stages of their research career post-PhD and is one of the most presitigious honors for early career scientists in psychology. Congratulations to them both!

A number of current and former lab members, including Steve Rathje and Claire Robertson, also presented at SPSP 2024 this year!

Papers & Preprints

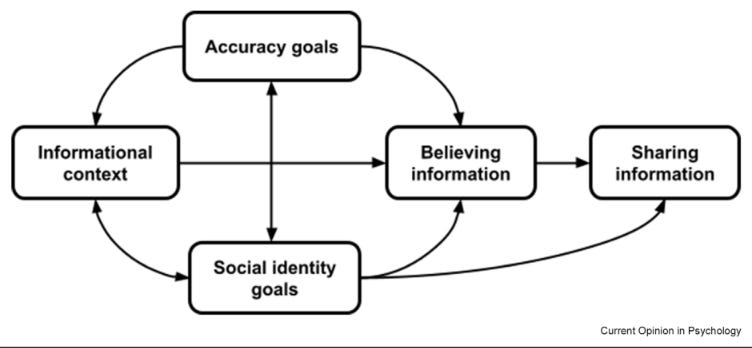

Our paper “Updating the identity-based model of belief: From false belief to the spread of misinformation” was also officially published in Current Opinion in Psychology! According to this model, social identity goals can override accuracy goals, leading to belief alignment with party members rather than facts. We propose an extended version of this model that incorporates the role of informational context in misinformation belief and sharing. Check out the official publication here.

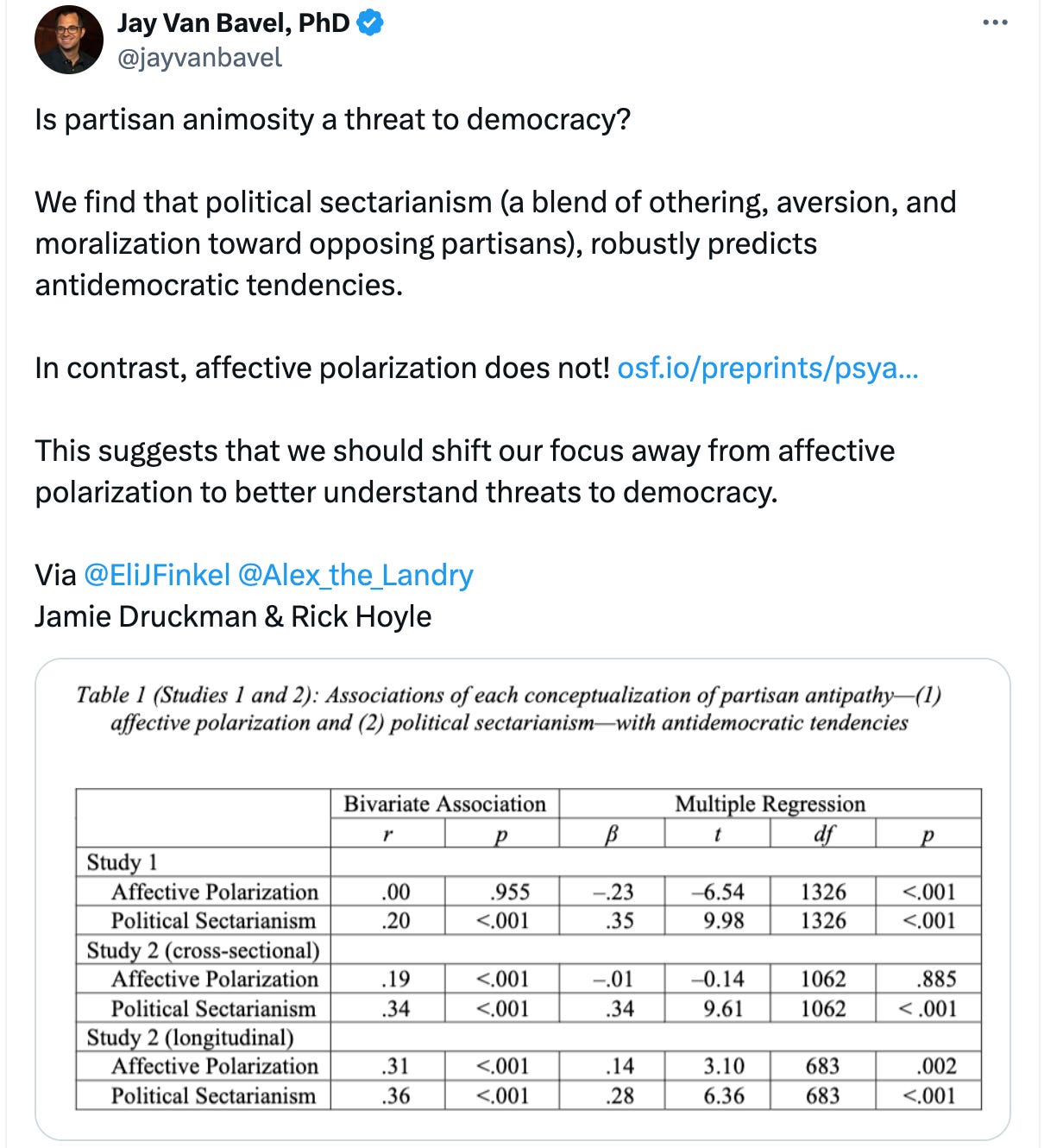

We have a new preprint out with Jay, Eli Finkel, Alexander Landry, James Druckman, and Rick Hoyle about partisan antipathy titled “Partisan Antipathy and the Erosion of Democratic Norms”, in which we find that political sectarianism (the othering, aversion, & moralization towards opposing party members) predicts antidemocratic tendencies, but affective polarization doesn’t.

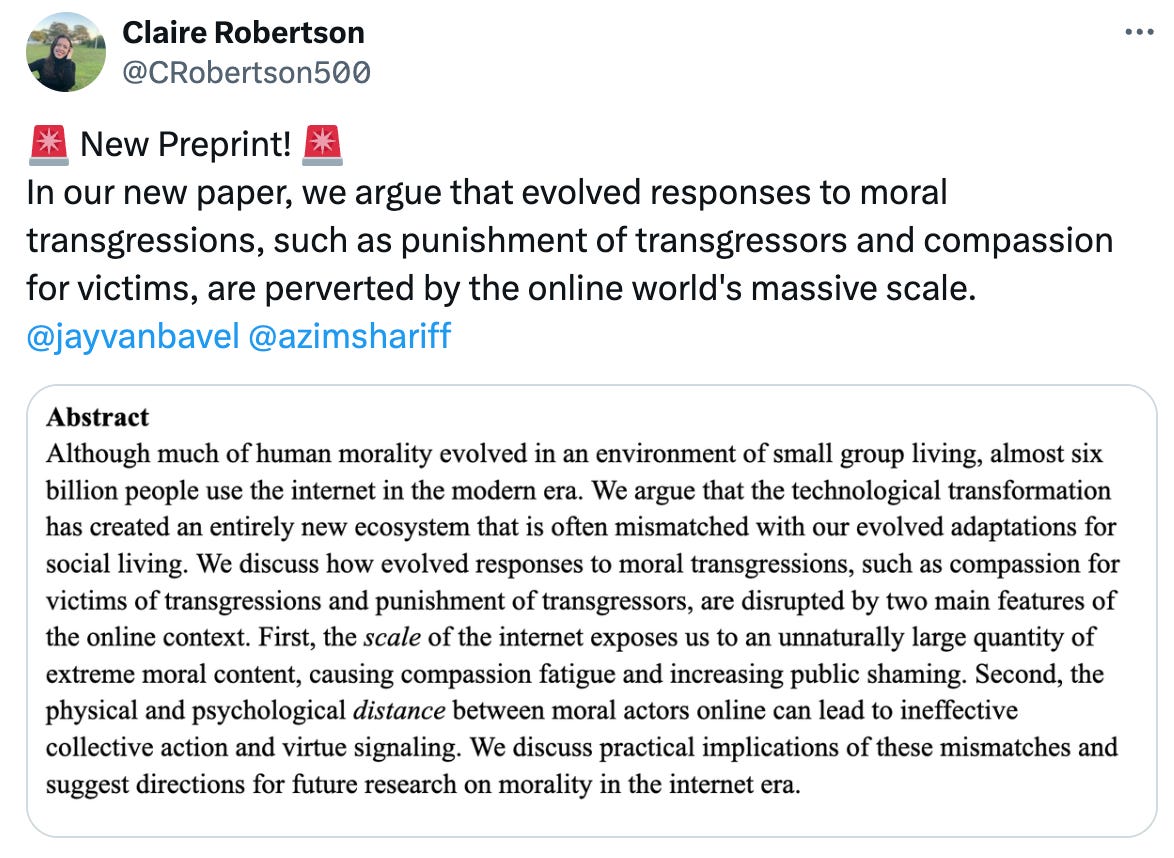

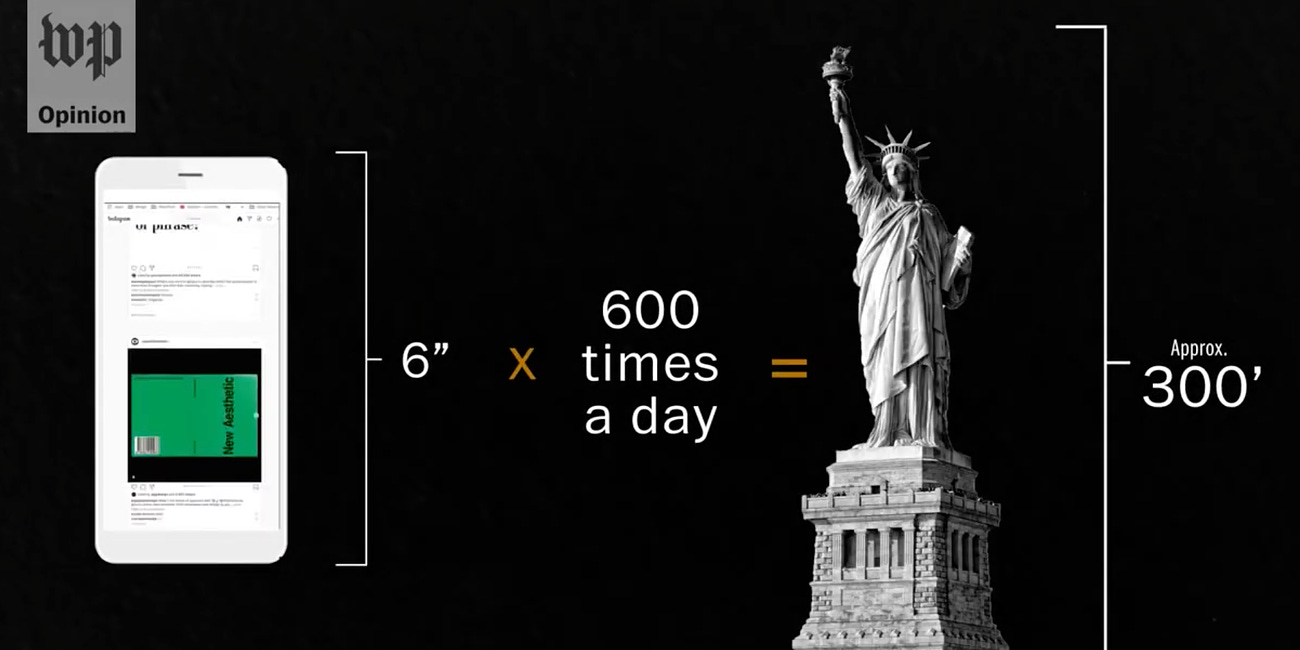

We also have a preprint titled “Morality in the Anthropocene: The Perversion of Compassion and Punishment in the Online World” with grad student Claire Robertson, Jay, and collaborator Azim Shariff. We argue that there is a mismatch between our evolutionary moral responses to moral transgressions and the sheer scale of the online environment, which leads to much of the anti-social phenomena we observe on social media today.

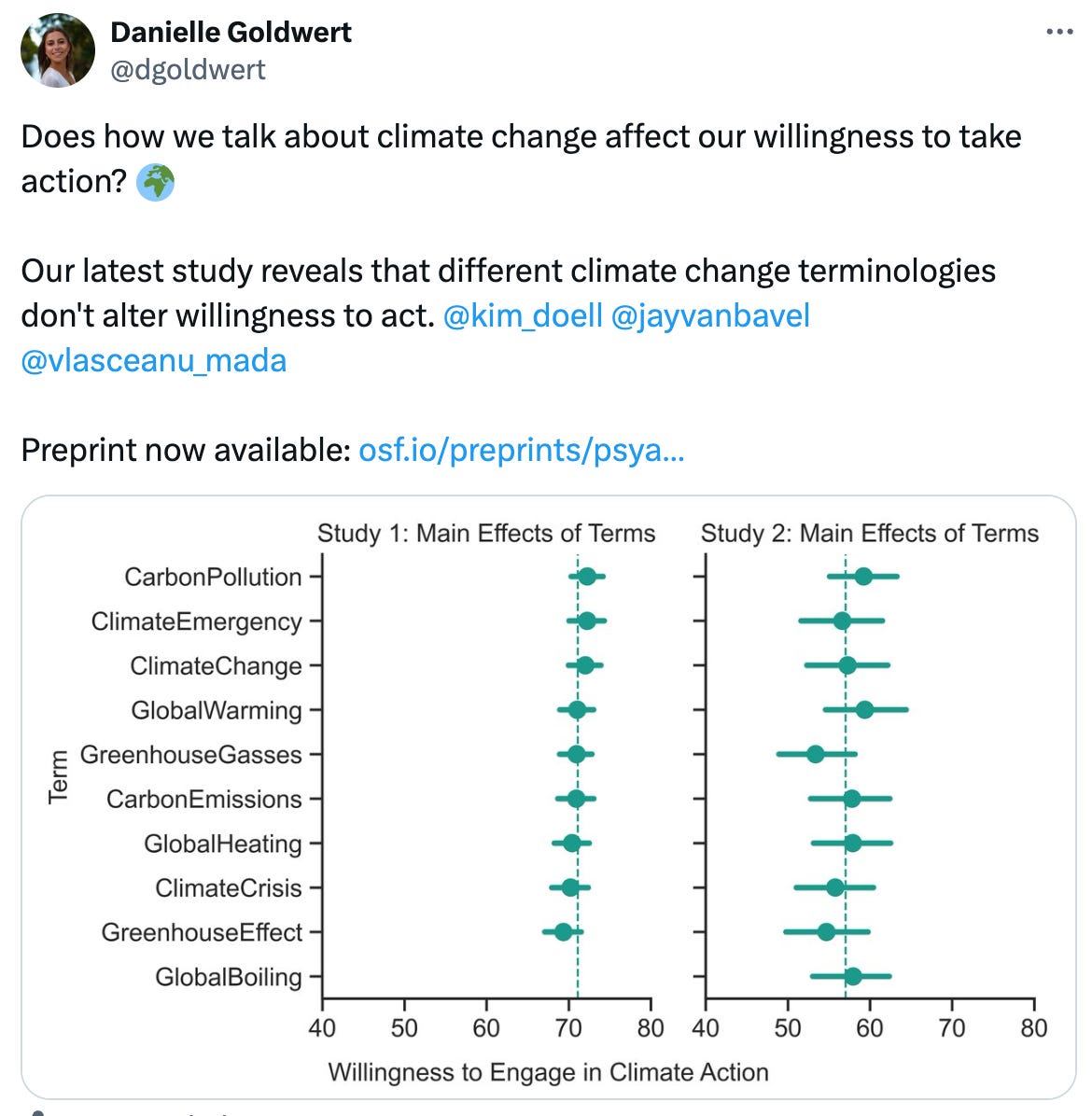

We have another preprint out with Danielle Goldwert, Kim Doell, Madalina Vlasceanu and Jay about the different terms we use to refer to the climate crisis. We find that none of the climate change terms we use actually influences willingness to take climate action! So maybe we should spend far less resources debating terminology and invest that into developing more effective messages and behavior change strategies.

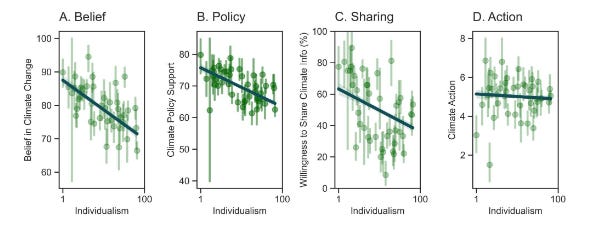

Another preprint that came out this past month, also led by Danielle and Evelina Bao, discussed the impacts of individualism and collectivism on the effects of different climate change interventions. We found that national levels of individualism were associated with greater climate change skepticism on three of our measures compared to collectivism. As such, individualism might be a real impediment to climate change mitigation efforts. You can check it out here.

If you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to our Lab Manager Sarah (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com) who puts together our monthly newsletter. We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

And in case you missed it, here’s our last newsletter:

That’s all for this month, folks- thank you for reading, and we’ll see you next month!