The real problem of humanity is the following: We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions and godlike technology. And it is terrifically dangerous, and it is now approaching a point of crisis overall. —Edward O. Wilson (cited in Harv. Mag. 2009)

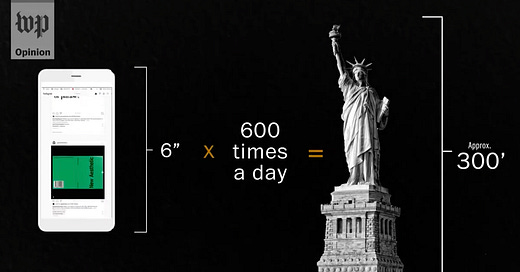

There are nearly 5 billion active social media users around the world. The average social media user spends a lot of time on social media, scrolling through an estimated 300 feet of content per day—roughly the height of the statue of liberty!

But how does the online environment shape human psychology? In our latest paper, we reviewed the literature regarding the relationship between social media and morality. This was our tour de force Jay wrote with Claire Robertson, Kareena del Rosario, Jesper Rasmussen, and Steve Rathje for Annual Review of Psychology.

This figure is from a video interview Jay did with the Washington Post

The main goal of social media platforms is to capture people's attention and monetize it through advertisements. However, humans have limits on what they can attend to at any given moment. This creates an attention economy on social media, where advertisers and other users compete for people's attention.

Competing in this attention economy can lead people to create and express exaggerated beliefs and carefully curated content designed to capture attention rather than reflect reality or benefit humanity. The pull of the attention economy is thus central to understanding the psychology and behavior of social media users.

One means by which individuals can capture attention and drive engagement is by sharing morally and emotionally evocative content. For instance, we have found that people will pay greater attention to moral or emotional words—and this is linked to what we share on social media.

Our actions on the latest technology are, of course, grounded in our Paleolithic emotions. We tend to pay more attention to morally provoking issues, as a result of evolutionary pressures that rewarded the ability to navigate social situations. This has raised the question: If moral outrage is a fire, is the Internet like gasoline, accelerating and exaggerating existing moral dynamics?

Our papers describes the psychological function and appeal of morality, and how these instincts are harnessed and monetized online. We also review the impact of moral psychology on a broad array of individual and societal issues related to social media. Finally, we discuss current and future directions of research on social media and morality. We review these issues very briefly here, but invite you to read the full paper over a glass of wine or whatever you fancy, if this sounds intriguing.

Origins of human morality

Moral psychology is the psychology of people's beliefs about what is right and wrong. Beliefs and social issues become moralized when they're framed as in the interests or greater good of something beyond an individual person, like social groups, networks, or all of society. Moral beliefs are also heavily influenced by social identities—like religious or political identities—and informs our politics. Identity and morality are particularly salient on social media, because people can easily signal their identities or beliefs to their social networks.

Beliefs that are rooted in our moral conviction or values are, naturally, stronger and more resistant to change than non-moralized beliefs. Morality also has a strong emotional component; these moral emotions are highly interpersonal, prosocial emotions since they're often motivated by a desire to defend the interests of others. Morality can be a force for positive social change, but it can also produce dangerous behavior—even allowing people to justifying violence towards their enemies.

Social conflict and polarization manifest online

With the advent of social media, our social interactions are increasingly moving online. People spend an average of nearly 2 and a half hours a day on social media and the internet is now the primary place where people encounter moral or immoral behavior—surpassing what we encounter in print, TV and radio combined!

Social media seems to reproduce and exaggerate the social behavior and dynamics that emerge from our identities, morality, and political polarization. For example, even though people display similar levels of hostility and political engagement on and offline, online discussions are perceived to be much more hostile. This might lead social media users to withdraw from social and political debates, and even exacerbate real world conflicts.

Due to the sheer size and rapid communication inherent of online social networks, people encounter more moral transgressions on social media than in real life. People may adapt to the complexity and large amounts of moral content on online networks by adapting a more generalizable morality, identifying people or groups as good vs. evil rather than as complex figures. Taken together, the online world appears to be driving much of our moral life.

Moral emotions capture attention online

Part of the reason that social media appears to inflame our moral beliefs and behavior is that we have a hard time ignoring moral content. For example, social media posts that contain moral-emotional language, and news framed through a moral lens are more likely to be shared on social media. And when we use moral emotional language, people see as hyper-partisan and close minded. Exposure to immoral events on social media might even make people likely to detect or interpret ambiguous moral content as they scroll through their newsfeeds.

Reinforcement and social norms increase moral outrage

Social norms are powerful drivers of human behavior. Since social status depends on adherence to norms, people will modify their behavior to gain the approval of others. The speed and scale of social media can accelerate the spread and enforcement of these norms, including moral norms. For example, social movements have organized social media hashtags that spread rapidly online and motivated collective action. This can lead to radical social change, like the #metoo and #BlackLivesMatter movements that spread on social media.

Social media can also accelerate mass harassment campaigns, mob behavior and conspiracy theories. This is known as morally motivated networked harassment, which is a mechanism to enforce norm violations using moral outrage. While moral behaviors like third-party punishment can signal trustworthiness and elevate status in social groups, the high visibility and low cost of engagement on social media makes it easy for large scale harassment campaigns to occur. Social media also amplifies conflict and exposes us to more aggressive individuals online. The reduced number of social cues in social media communication and anonymity on social media may also contribute to inflated perceptions of online outrage.

Although social media can facilitate outrage, norm enforcement, mass-scale harassment, and public shaming, this has unintended—and often surprising— consequences for moral judgment. For instance, the larger the number of people who publicly criticize a moral transgression, the more likely third parties are to empathize with the original perpetrator of the transgression. They can thus view a transgressor as a victim of bullying, garnering them more sympathy than they would have otherwise. Something to think about before you join the next online pile on.

Design features and algorithms may amplify moral content and conflict

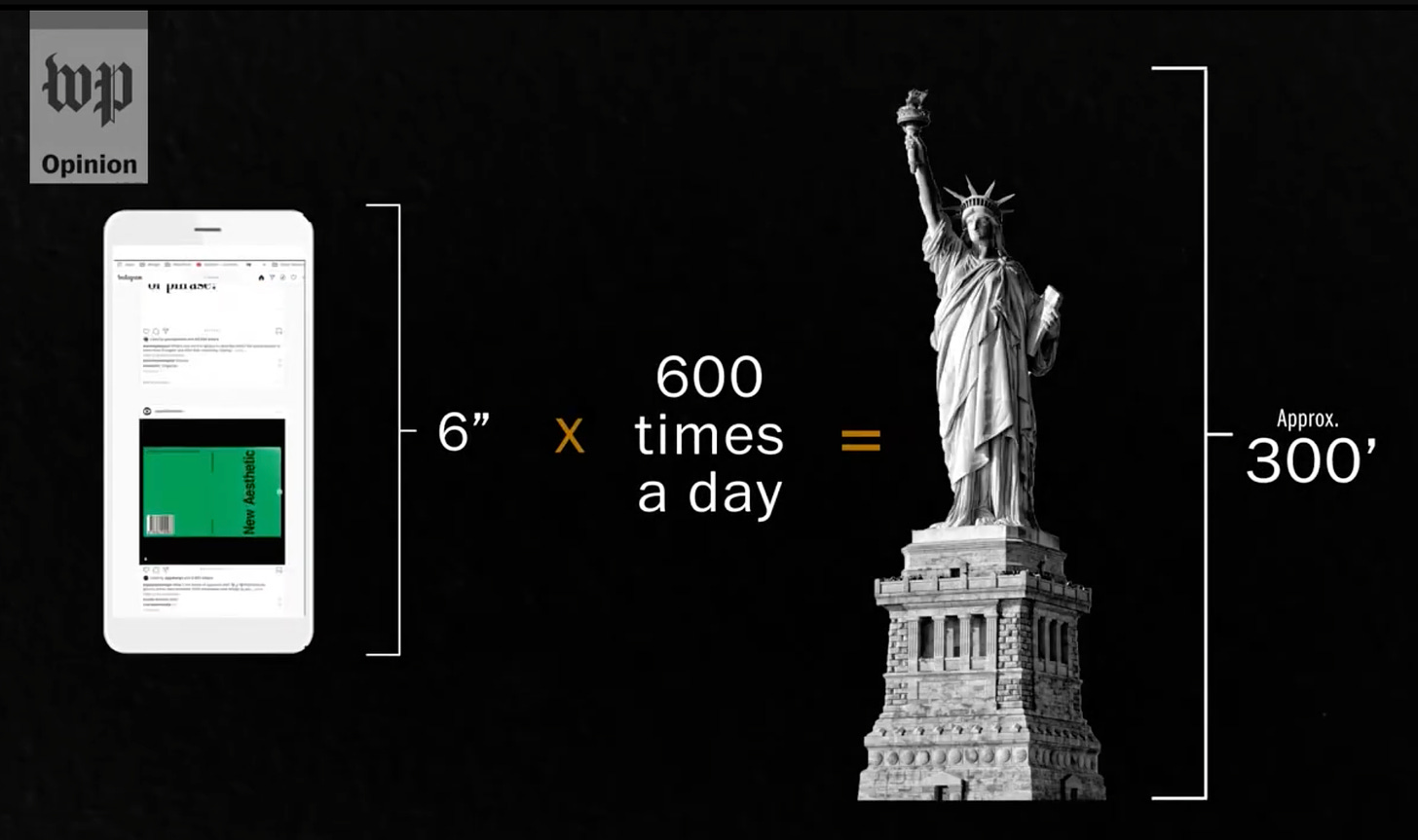

The design and incentives of social media accelerates moral content. Hostile conversations may be amplified by social media algorithms if they generate engagement, and shaming political opponents seems to be a key driver of engagement on social media. This is why out-group animosity appears to be one of the strongest predictors of online engagement—increasing the spread of news stories by 67%!

Social media algorithms also promote related ideological content, which may lead to people expressing more outrage than they actually feel and creating inflated norms of outrage expression online. These expressions of outrage, like comments, likes, and shares, are low cost forms of engagement that receive more positive feedback, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of outrage expression.

There is serious debate regarding whether social media fosters 'echo chambers' online. Whether or not people are exposed to more cross-cutting or politically congruent information online seems to vary across platforms, underscoring the need for more research on differences between platforms. It is also unclear how breaking down echo chambers might impact moral psychology. Exposure to diverse viewpoints might reduce polarization, but some research has found no effect—or even a backfire effect where people become entrenched in their own beliefs.

Motivations for expressing outrage

People express outrage online for many different reasons. Outrage can be motivated by both selfless goals (to bring attention to injustice, mobilize collective action, etc.) and selfish goals (to demonstrate moral superiority, gain social status, etc.). It can be driven by intrinsic ideological goals, where people raise awareness about an issue regardless of potential personal or professional consequences, as well as extrinsic goals. Distinguishing between these motivations in an online context is extremely difficult and it might lead to generalized cynicism about ‘virtue signaling’.

Moral grandstanding (meaning the pursuit of social status through moral reputation) can trigger outrage online at a far greater scale than the inciting incident deserves. When people express outrage, they are perceived as having greater conviction in their moral values. Others may therefore join in on the discourse without making meaningful contributions, benefitting from the situation in a phenomenon called free riding. Social media encourages collective expressions of outrage because users are primed to interpret everything through a moral lens, and are rewarded with likes, comments, and engagement.

Individual differences in online morality

Individual differences also shape the relationship between social media and morality. Virtuous victim signaling—where people portray themselves as a trustworthy person to gain moral status and sympathy—is associated with machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy. People who are aggressive and hostile in real life also tend to display those behaviors online. However, they can be more visible online and harass others at a scale that is difficult to match in real life encounters. They can also do it with impunity in many online contents.

While personality traits are important to consider when discussing aggression and moralized behaviors on social media, people also act this way to further their political causes. Hate speech and misinformation often increases during elections and times of political turmoil, and partisan polarization appears to be one of the primary psychological factors driving fake news sharing. Thus, moralized political discussions on social media might amplify, reward, and select for people with certain traits.

Extremists dominate online conversations

Moral discourse online is dominated by ideological extremists, who show higher levels of outrage on social media compared to moderates. Because of the amount of people on social media, there are far more extreme voices to affiliate with than ever. Social media feeds can then become saturated with extremists' posts, who are dogmatic and tend to present their beliefs as facts. This may have a polarizing effect on moderate users.

Social media might also cause people to see more divisive and polarizing content than they actually want to see. People report that they don't think negative, divisive content should go viral, but it does anyway. Instead, they want accurate, thoughtful, or nuanced content to go vial online, but believe it does not go viral.

Consequences of social media

While the rapid spread of moralized content online has many negative consequences, it has led to many positive ones as well. It is therefore important to balance the moral tradeoffs of any new technology, and develop practices and regulations to offset any harm. But what are some of the positive and negative consequences of social media?

Social media enables the rapid spread of information to a large number of people faster than ever before. Online platforms can enable marginalized voices to find social support and mobilize large protests and collective action.

However, it could also have a negative impact on protests. Non-violent protests are easy to organize on social media without leadership, but lack of leadership can lead to social movements fizzling out without any substantive policy achievements. Additionally, moral outrage is often directed at multiple issues which might dilute collective efforts and dissipate attention across social issues. Social media platforms can also give bad actors a platform to spread harmful misinformation and propaganda, even inciting real-world violence.

Social media algorithms also prioritize the spread of emotional, polarizing, and attention-capturing information, which distorts the quality of the information people consume online. In particular, the spread of moral and emotional content online is also to increasing political and affective polarization. Moral-emotional words (like “hate” and “blame”) are more likely to spread within online “echo chambers” than across party lines. When people don't use moral-emotional language to discuss the same political issues, there is little evidence of polarization occurring along partisan or ideological lines.

Conspiracy theories, which are often motivated by moral concerns, can go viral rapidly on social media. Even fact-checked false stories can spread faster on social media than fact-checked true stories, especially for emotional stories on political topics. Misinformation and moral outrage are also closely intertwined; misinformation containing moral outrage is more likely to spread on social media. This also has substantial consequences for public health. For example, misinformation on social media is associated with greater vaccine hesitancy and reduced intentions to get vaccinated. During the COVID-19 pandemic, polarized rhetoric about the pandemic on Twitter was highly correlated with polarized beliefs about the risks of the pandemic several days later.

Future directions

There are multiple ways to lessen the negative consequences of the relationship between morality and social media. Legal regulation is one heavily debated way of reducing the adverse effects of social media. A number of psychological interventions for these effects have also been tested, such as bystander interventions that encourage people to denounce hostility online. Finally, adjusting the algorithms and incentive structures that govern social media can encourage people to act more positively online.

Finally, there are a number of future directions for research on social media and morality. The vast majority of the research done about social media and polarization is from the United States; thus, cross cultural studies are sorely needed to examine how culture affects the interplay between social media and morality. There has been little cross-platform research on social media and morality, partially due to lack of data access and transparency from companies. More experimental field research on social media is needed to understand the consequences of social media use at the individual and societal level. Finally, interdisciplinary work is also necessary to fully understand how social media impacts individuals, groups and societies.

However, we think this is a critically important and rich area for future research. It is only by understanding the impact of social media—and it’s interplay with human psychology—that we can build more humane technology that allows people and society to flourish.

You can read the full paper or preprint using the links here: Van Bavel, J. J., Robertson, C., del Rosario, K., Rasmussen, J., & Rathje, S., (2024). Social media and morality. Annual Review of Psychology, 75, 311-340. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-022123-110258

New Papers & Preprints

We are also also excited to share our new paper, entitled “The Misleading count: an identity-based intervention to counter partisan misinformation sharing”, which tested an identity-based intervention for polarizing misinformation on social media. It was officially published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B this month!. You can check it out here.

We also had a pre-print of our adversarial collaboration come out, entitled “On the Efficacy of Accuracy Prompts Across Partisan Lines: An Adversarial Collaboration”. It tested the effect of accuracy prompts on news sharing across partisan lines. You can read it here.

Another preprint about the data collected for the climate interventions mega-study was published here, if you’d like to check it out. This project was a real beast and we will have a detailed write up in a future newsletter.

In the News

Psychology Today wrote an article about a review that lab members Jay Van Bavel & Steve Rathje, and lab alums Clara Pretus, Madalina Vlasceanu, & Philip Pärnamets co-authored about political polarization during the COVID-19 pandemic. You can read it here.

Jay was interviewed by Poker Champion and Best-selling Author, Annie Duke, about the effects of group identities, values, and beliefs, especially in politics. Read their conversation here.

Finally, Jay was also featured in an article from the APA’s Monitor on Psychology regarding misinformation in the upcoming election year. Read more here!

If you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to our Lab Manager Sarah (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com) who puts together our monthly newsletter. We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

And in case you missed it, here’s our last newsletter:

That’s all for this month, folks- thank you for reading, and we’ll see you next month!