Top tips for navigating your career: The Hidden Curriculum

We summarize our career advice on everything from writing effectively and giving a stellar presentation to writing a CV and negotiating a job offer

Have you ever wondered how academics nail their invited talks, publish paper after paper, or manage to land a job in the competitive academic job market? Academia is a unique field that requires many different hats and lots of unspoken knowledge–which is often described as the “hidden curriculum” In an effort to demystify the Ivory Tower, Jay and some other colleagues wrote a series of columns for Science Magazine. In this month’s newsletter, we summarize each one.

We have general advice that should be helpful for a broad audience on giving great presentations, writing efficiently, goal setting, saying “no”, managing conflict, and mentoring, as well as specific advice for each academic career stage including applying to graduate school, negotiating a job offer, and running a lab. Whether you are just starting to consider graduate school or preparing your tenure materials, this is a roadmap to navigate the hidden curriculum

To read the full column, just click on each header!

Introducing ‘Letters to young Scientists’, a new column from Science Careers

Kicking off the series is the very first column, where each of the 5 contributors introduce themselves and establish the inspiration for starting this column! The contributors are Will Cunningham (Professor of Psychology at the University of Toronto), June Gruber (Associate Professor of Psychology & neuroscience at the University of Colorado in Boulder), Neil Lewis, Jr. (Associate Professor of communications & social behavior at Cornell), Leah Somerville (Professor of Psychology at Harvard), and Jay Van Bavel (Professor of Psychology & Neural Science at NYU). The column was inspired by a long tradition of past generations of prominent scientists writing advice for new and upcoming scientists.

FOR UNDERGRADS:

Applying for a Ph.D? These 10 tips can help you succeed

Navigating the endless application guidelines for Ph.D programs can be an extraordinarily daunting task, so we offer 10 key guidelines applicable across multiple fields of study and schools, to help prospective students prepare the best application they possibly can. These include honing your research statement by asking for feedback from professors and current graduate students, finding departments where you would be interested in working with multiple faculty members, and being true to yourself. We acknowledge that the Ph.D journey is best if you are deeply passionate about scientific research and open to a variety of careers.

To ace your Ph.D program interviews, prepare to answer—and ask—these key questions

You’ve made it past the first round of admissions and finally arrived at the interview. But remember, you’re not only demonstrating how you'd fit into the program, you’re also assessing the program’s fit for you. You should be prepared to answer questions about why you’re applying to graduate school, your career goals, and what research you’d like to pursue. But, you should also prepare questions about things you want to know, like if the training provided fits your goals for after graduate school, and if the culture of the program is supportive.

FOR GRADUATE STUDENTS & POSTDOCS:

How to navigate conflict with your research adviser

Mentorship can be a tricky thing to navigate in academia. In this article, we break down different strategies to approach your advisor based on whether they’re a good, bad, or toxic advisor, and offer advice to current mentors on how they can better their own mentorship. If you have a good advisor, it’s always best to assume good intentions when there’s conflict. But, if you have a bad or toxic advisor, you may need to consider other mentorship options in order to continue your academic journey.

How to find a postdoc position that’s right for you

Finding a postdoc position can be less straightforward than applying to faculty positions or graduate school. If a postdoc position would help you work towards your long-term goals, we lay out some tips for finding a postdoc position that’s right for you. You should come up with a list of options. Some academics use a postdoc as a way to transition into a new area of focus for their research. Funding is another important consideration—finding your own can be stressful, but might give you more freedom than a predetermined postdoc position for a specific project.

In the tough academic job market, two principles can help you maximize your chances

The academic job market is competitive and tough to navigate, with random events making it difficult to pin down what works. To increase your chances of landing that interview, it’s important to maximize your signal for what works, and minimize the noise to account for the random factors that affect any job search. You can maximize your signal by crafting your materials to make it easy for any committee reviewing your application and getting feedback on your materials. And, you can minimize the noise by applying to a wide variety of jobs over multiple job cycles, if possible.

How to put your best foot forward in faculty job interviews

It’s really exciting to receive an interview offer after spending ages laboring over your application materials for a particular job posting! Knowing what the interview will be like can help you figure out where to invest your energy in preparing. Here we describe how common faculty job interviews tend to go, such as a colloquium-style lecture about your research and a day of meetings during an in-person visit. The best thing to do is practice over and over again, and prepare by doing your research on who you’re meeting with in advance.

Ten tips for negotiating job offers

After the excitement of receiving a job offer fades, many scientists are unsure of how to negotiate their offer. Here we offer some tips if you’re new to the art of negotiating a job offer. For example, it’s important to do some research about how negotiations work and your value on the job market. You can also negotiate more than just your take-home salary; academic negotiations often include start-up research funds, relocation costs, lab and office space, and travel funds. You should negotiate with confidence, and use any other offers you may receive as leverage to get a better package from your preferred position.

FOR FACULTY

Three keys to launching your own lab

Getting to launch your own lab is an exciting step forward in your academic career, that you often aren’t explicitly trained for. As you get started, be sure to take advantage of all the resources available to you so you can tackle any potential challenges in your new environment. It’s easy to get trapped in the enormous amount of decisions to be made; just getting started on doing anything can be helpful to avoid decision paralysis. Finally, being deliberate about setting up a supportive lab environment with clear expectations can help set up your lab for success in the years ahead.

How to foster healthy scientific independence for yourself and your trainees

While science is inherently a collaborative discipline, learning how to conduct your work without close supervision or oversight is an important part of scientific training. Here we offer advice on how to foster that scientific independence. One good way to start out fostering that independence is by leading a research project on more original work that doesn’t align as closely with your mentor’s work. You can build on that work as you move into becoming a faculty member and develop a unique research direction. As a mentor, it’s important to let your trainees try their hand at writing their own grants, focusing on the collective success of your lab members.

Three research-based lessons to improve your mentoring

Mentorship in academia can vary between the good, the bad, and the ugly. Learning the science behind good mentoring can help anyone from senior professors to graduate students mentoring their research assistants become a better mentor. For example, we can take lessons learned from research on relationships by providing engagement and support alongside achievable high expectations. Conveying your belief in your student’s abilities and potential, and helping your mentees embrace failure as growth is also vital.

Conflict in your research group? Here are four strategies for finding a resolution

Unfortunately, science is not a purely collaborative environment. Inevitably, conflicts between lab members arise, and it’s important to constructively and effectively deal with such conflict. We offer some tips for managing conflict in a research setting in this article, such as assuming good intentions on the part of the members involved, and listening carefully before making comments, especially if you occupy a position of power in the lab. It may be necessary to document what happens in case the matter needs to be escalated to the university.

FOR ALL CAREER STAGES:

How to write a clear, compelling CV

A polished CV is essential in academia. It provides a far more exhaustive list of a scientist’s credential’s than a typical resume can, including degrees, positions, publications, and presentations; teaching, mentoring, and service activities; and other relevant categories. When writing your CV, it’s important to start with some introduction information like your name, current title and affiliation, and a short summary of your interests and expertise. The order of your sections is also important, since people are more likely to remember the beginning and end of your CV; remember to highlight important information using formatting and stylistic choices. Our last tip is to make sure you continually update your CV by both adding recent accomplishments and trimming older entries for conciseness.

A social media survival guide for scientists

Social media is both a wonderful platform to engage all kinds of people with your scientific research, and a wonderful place to get stuck arguing over rage bait with trolls. Here we offer some advice on how to navigate social media as an academic, like remembering that everything is forever on the internet—so be careful about what you post! It’s also worthwhile to curate your feed by following scientists, labs, journals, and companies that are interesting and relevant to your work; you might come across opportunities that you never would have otherwise.

Step back to move forward: Setting new goals and priorities

This column offers advice on how to step back and reassess your priorities. After taking time to step back and think about the future you want to achieve, it can help to create plans for your next few months and years ahead to determine if the things you’re spending time on in the present, are aligned with those longer-term goals. Breaking down those goals into short-term, concrete tasks and encouraging yourself even when you get off track is key.

Three tips for giving a great research talk

Great research talks can engage the audience regardless of their background knowledge of the topic, and get the point of the presentation across with precision and conciseness. To do so, you should find a central focus or takeaway for your talk that’s relevant for the audience you’re speaking to. You should present your information clearly, and make sure the details are right for the audience. For example, specialists may be interested in the details of how you conducted your research, but a more general audience might be bored by those particulars.

Struggling with your academic writing? Try these experiments to get the words flowing

Writing up results in a scientific paper is one of the most important skills you can polish for your academic career. This article offers several ways to enhance your writing skills and output, like embracing the process of revision, or creating a writing group to hold yourself accountable for your writing goals.

Help funders help you: Five tips for writing effective funding applications

Even if you’re not familiar with writing grant proposals to get funding for your research, you’ve probably already gained experience with the basic skills required over your academic career. Pitching a grant to be funded is not so different from persuading an admissions committee to admit you as a graduate student, or convincing a PI to take you on as a postdoc. Your grant proposal should have, among other things, a clear, testable idea and reasoning behind why testing the idea is important. It’s good to know your funder’s priorities and tailor your proposal accordingly. Like everything, it’s important to be persistent!

A scientist’s guide to email etiquette

Whether you love it or hate it, email makes up a substantial part of being a scientist. Written communication carries with it lots of pitfalls, like a failure to properly convey tone or the potential to erode your work-life boundaries. We offer some tips to manage the deluge of emails you might have on a daily basis, like maintaining professional signatures and writing emails that are concise and courteous. It’s also important to maintain strong work-life boundaries especially in regard to emails; turning off your notifications during your off time or when you need to focus could be beneficial.

How to be an ethical scientist

True discovery takes time, has many stops and starts, and is rarely neat and tidy. It’s easy to forget this, however, when there’s constant pressure in academia to “publish or perish”. We offer some items to reflect on that will allow you to succeed without impairing the broader goals of science. For example, it’s always good to be open to being wrong, and to not overstate your findings. Getting critical feedback and being transparent can help your scientific work be as rigorous as possible.

Tips for easing the service burden on scientists from underrepresented groups

The work force of academia is often less diverse than the population it draws from. Many departments in academic institutions employ scientists who are the only ones identifying as a member of a particular group (like race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.), also referred to as being a “solo-status scientist”. Such scientists often perform more service duties than their colleagues, which ends up being time taken away from the activities that are more likely to impress tenure granting committees. This article provides both advice for solo-status scientists who might have additional representative burdens placed on them, and guidelines for their colleagues and academic institutions on how they can reduce the unfair service burden on existing solo-status scientists.

School’s (somewhat) out for summer: Five tips to help make the most out of the season

Summertime is a much more free time for academics. On one hand, it feels like you have all the time in the world to get around to tasks you couldn’t do in the academic year; on the other the lack of structure can lead to a “summer slump”. Some ways to make the most of your summer break include maintaining a structured schedule, taking stock of your current projects to plan out next steps, and actually taking some time off to avoid burnout!

Learn when–and how–to say no in your professional life

It’s tempting to say yes to everything in your early career, especially in academia. However, doing so can easily overwhelm you and reduce the time you have for your core commitments, like writing or mentoring. Before taking on more responsibilities, it’s worthwhile to consider the pros and cons of what’s being proposed to you. It can be scary and difficult to say no as an early-career scientist- so, finding more knowledgeable allies who can help advise and advocate for you can be invaluable. Figuring out how to say know can save you the awkward experience of ghosting a request simply because you didn’t know how to respond, or saying yes just to avoid saying no!

Science relies on constructive criticism. Here’s how to keep it useful and respectful

None of our scientific ideas are perfect, which means they are all destined to be questioned, reinterpreted, and potentially discarded. There are good principles to follow when giving criticism to help reduce some of the anxiety and stress from receiving it. It’s helpful to construct your feedback to minimize personal attacks and focus on being constructive. Embracing intellectual humility and assuming the best of what you’re critiquing is also helpful. When receiving criticism, it’s important to avoid getting defensive and to not take any critiques personally.

Scientists have passions outside the lab. We should embrace that

In this column, Jay discusses a former post-doc who felt conflicted about sharing news that she had published another fiction book successfully. She felt that sharing this accomplishment might paint her as a scientist who wasn’t as rigorous or devoted to their work compared to others. But, it’s important for everyone in academia to embrace passions outside the lab, for the sake of our working culture and our mental health.

My lab group met to chart our response to COVID-19. Here’s what we learned

In one of the first columns published during the COVID-19 pandemic, Jay describes the steps he and the lab took to figure out how to map out changes to their research program during the pandemic. Written in a time of uncertainty, it’s a fantastic look at how our lab group came together to support one another and change course during a life-changing global crisis.

Academia needs a reality check: Life is not back to normal

In this article published during the pandemic, we emphasized that life was not yet back to normal even if universities were welcoming students back to campus. We offered three principles to keep in mind during that tumultuous time, like acknowledging that things are not back to normal in a stressful and unprecedented pandemic; respecting child care and other personal needs that people may have; and triaging what work is essential and reasonable to complete. These principles can be applied to any time where external circumstances exert stress on your academic community.

Why the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to overdue change in academia

In the last of our columns written about the COVID-19 pandemic, our columnists have a conversation to discuss what the pandemic changed about the functioning of their labs, and what changes they intended to keep moving forward.

This section was drafted by Sarah Mughal and edited by Jay Van Bavel

New Papers & Preprints

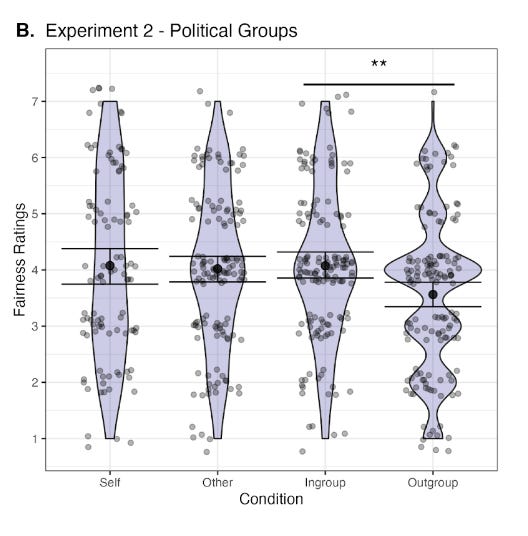

Our pre-registered replication of “Moral Hypocrisy: Social Groups and the Flexibility of Virtue., was officially accepted for publication in Psychological Science! While we failed to replicate some of the key findings, we did find evidence of intergroup moral hypocrisy in both studies. Specifically. we found that political groups were less forgiving of the exact same moral transgression when it was committed by an outgroup member compared to an ingroup member. This paper was written by Claire Robertson, Madison Ackles, & Jay Van Bavel. You can read the preprint of the paper here.

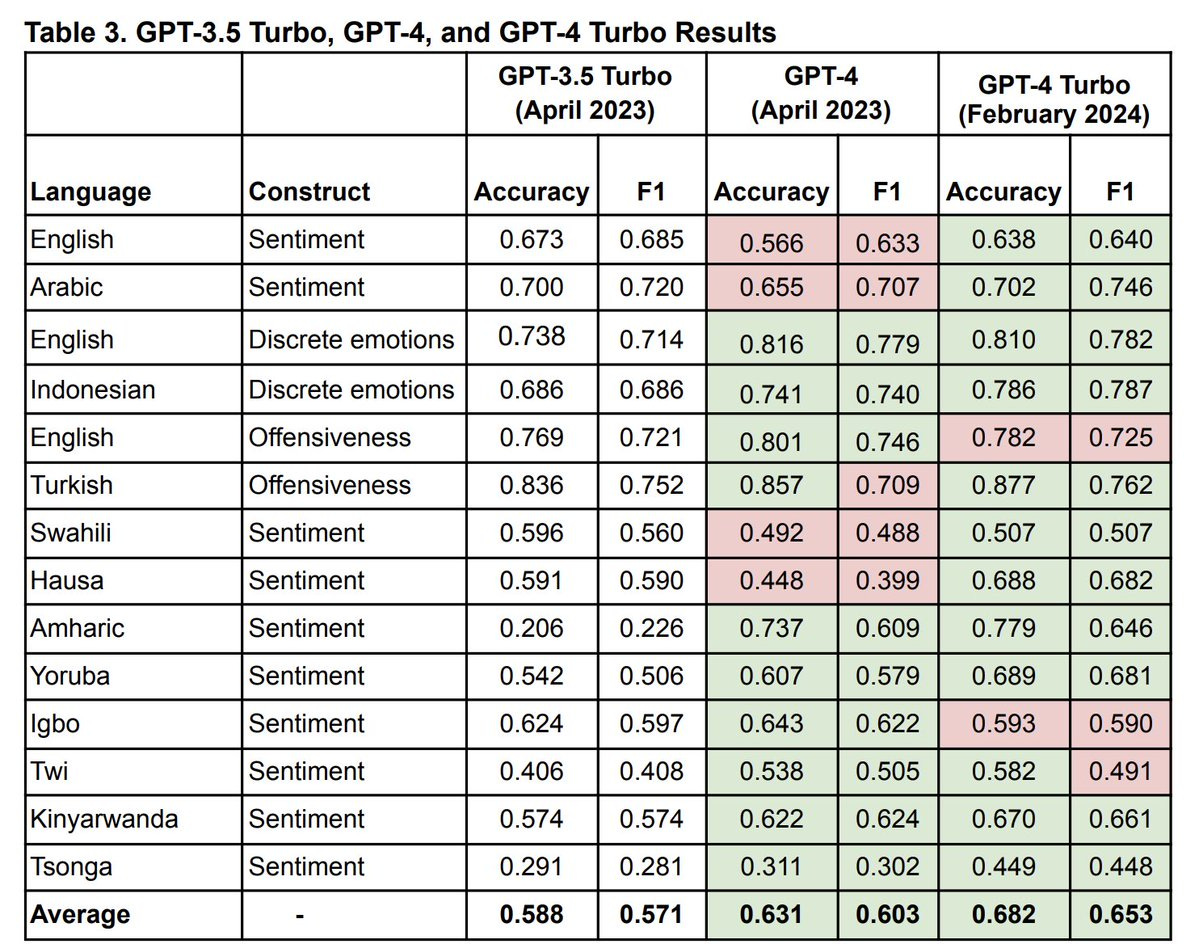

We updated our preprint on using GPT for text analysis (e.g., analyzing concepts like emotions, sentiment, and offensiveness). The paper now includes new results from GPT4 Turbo, and incorporates more discussion on GPT’s potential weaknesses and biases. Crucially, we found that GPT-4 Turbo does even better than GPT-4 in detecting psychological constructs via text. The paper was led by Steve Rathje and Dan-Mircea Mirea. You can read our updated preprint here.

Other Announcements

Recently we invited Laura Kriska, an organizational consultant and author of The Business of We, to evaluate our group performance using her Team Machine exercise. This exercise is designed to evaluate team cohesion and foster connections among groups. We had to break into small groups to make a component of a Rube Goldberg machine and then all come together to form the pieces into a single machine. It was a blast to have her and her associate Heather for our lab meeting, and according to her we did fantastic compared to her other groups. In fact, she said we were the fastest and most effective team she’s ever assessed (including leading engineering firms and executive teams)! Find out more about Laura and her work here.

Jay gave a keynote address about his book “The Power of Us” at this year’s American Montessori Society conference. He shared research from the lab on the need to have shared goals, collective rewards, healthy social norms and excellent leadership to build healthy and effective groups with over 400 teachers!

If you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to our Lab Manager Sarah (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com) who puts together our monthly newsletter. We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

And in case you missed it, here’s our last newsletter:

That’s all for this month, folks- thank you for reading, and we’ll see you next month!