Social identity shapes your belief in fake news

Partisan bias in fake news belief and sharing, an identity-based intervention against fake news, how to go viral on TikTok, and introducing our lab's newest PhD, Dr. Elizabeth Harris!

When Elizabeth Harris first thought about getting her PhD in social psychology, she didn’t necessarily think she wanted to study fake news. She was interested in moral psychology—the study of how people form moral beliefs, how these beliefs may change, how issues become moral issues—and our lab seemed liked a good fit.

But she also happened to be applying to doctoral programs in the fall of 2016: the season of the federal election between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, a time of increasing polarization and online misinformation. It felt like an emerging “post-truth” era, particularly in the United States.

For Elizabeth, studying these issues took on a new sense of urgency. She had always been interested in partisan identity—when people identify with political groups—and its impact on how we experience the world. But by the time she entered graduate school, it became increasingly clear to her how little we understand the psychological reasons of how, when, and why people believe and share fake news. She began to focus on how our identities influence our perceptions of the information we consume—and importantly, why we share this information with our social networks.

Over the past five years, Elizabeth has become the resident fake news expert in our lab and successfully defended her PhD dissertation last week (see pictures below). Her dissertation focused on her work on partisanship and fake news belief and sharing. We decided to share a bit of her dissertation here to help you understand the importance of partisanship and how it may shape your perception of information:

How partisanship works

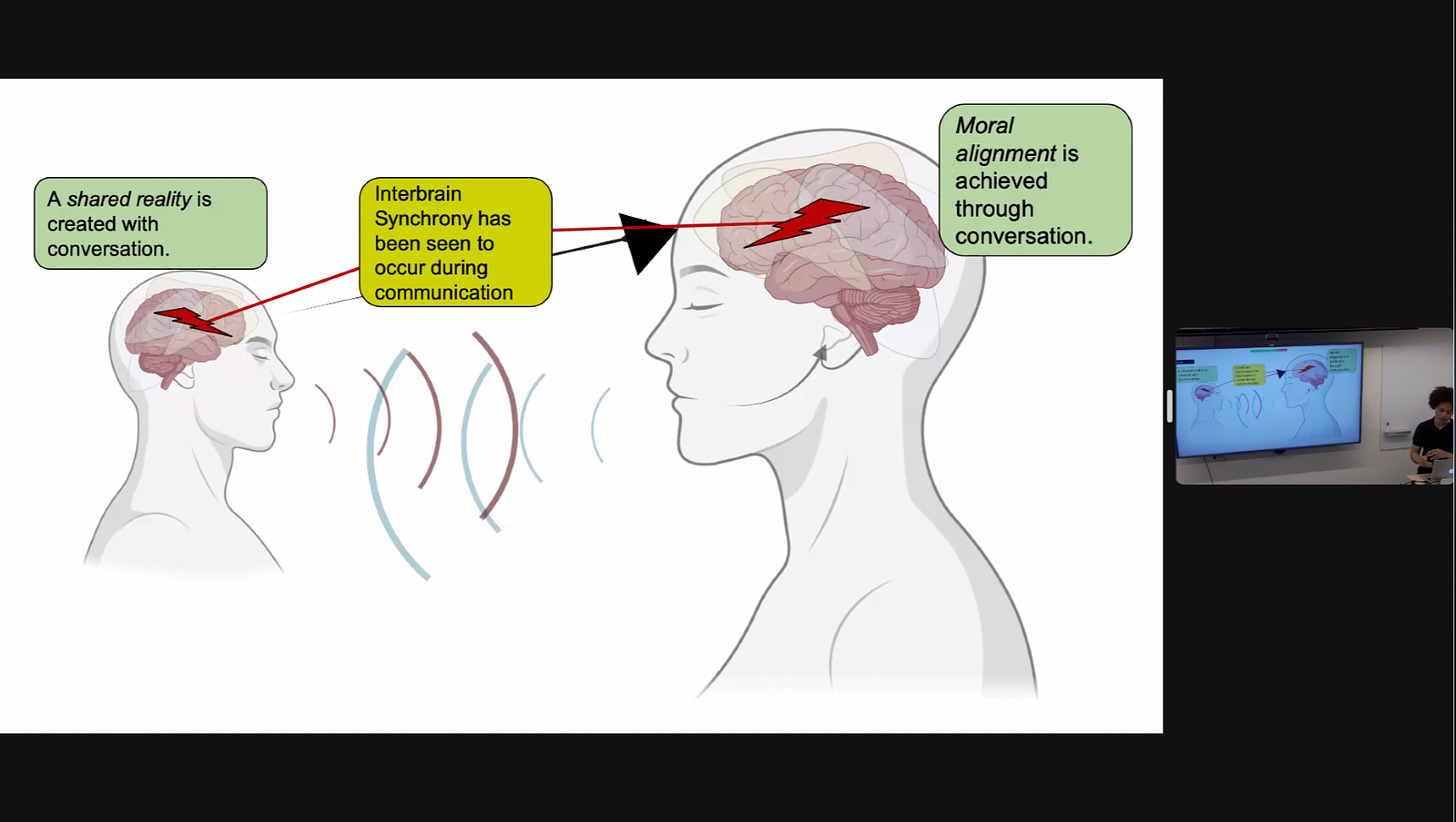

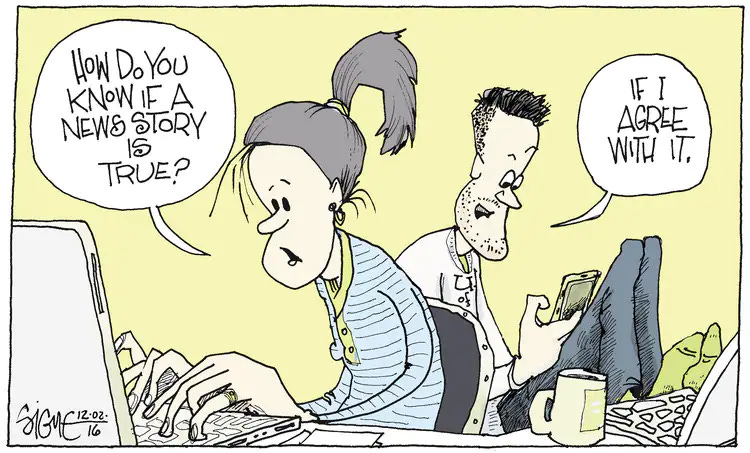

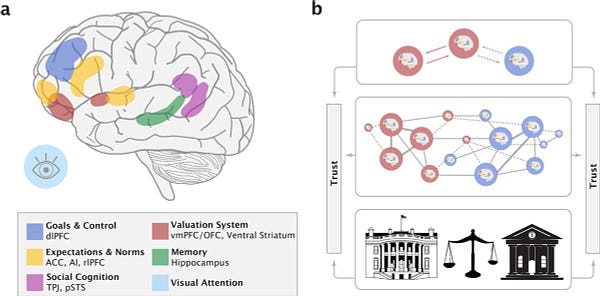

To understand how partisanship works in the mind and brain, we have to return to one of the most fundamental theories in psychology: Social Identity Theory. According to Tajfel and Turner, people are prone to form social groups and form attachments towards these groups—often resulting in in-group bias, or a preference favoring in-group members. These groups can be meaningful social categories (i.e. race, gender), but the effects of social identity can even extend to seemingly meaningless groups (i.e. red-shirts vs. blue-shirts in an experiment).

Members of political groups behave and think in ways that are consistent with the tendencies related to basic social identity, demonstrated by research on intergroup discrimination and how partisan groups are represented in the brain. In political contexts, these tendencies are amplified by competition for scarce resources, different moral values, and intersections with other identities—for example, national identity, religion, and race.

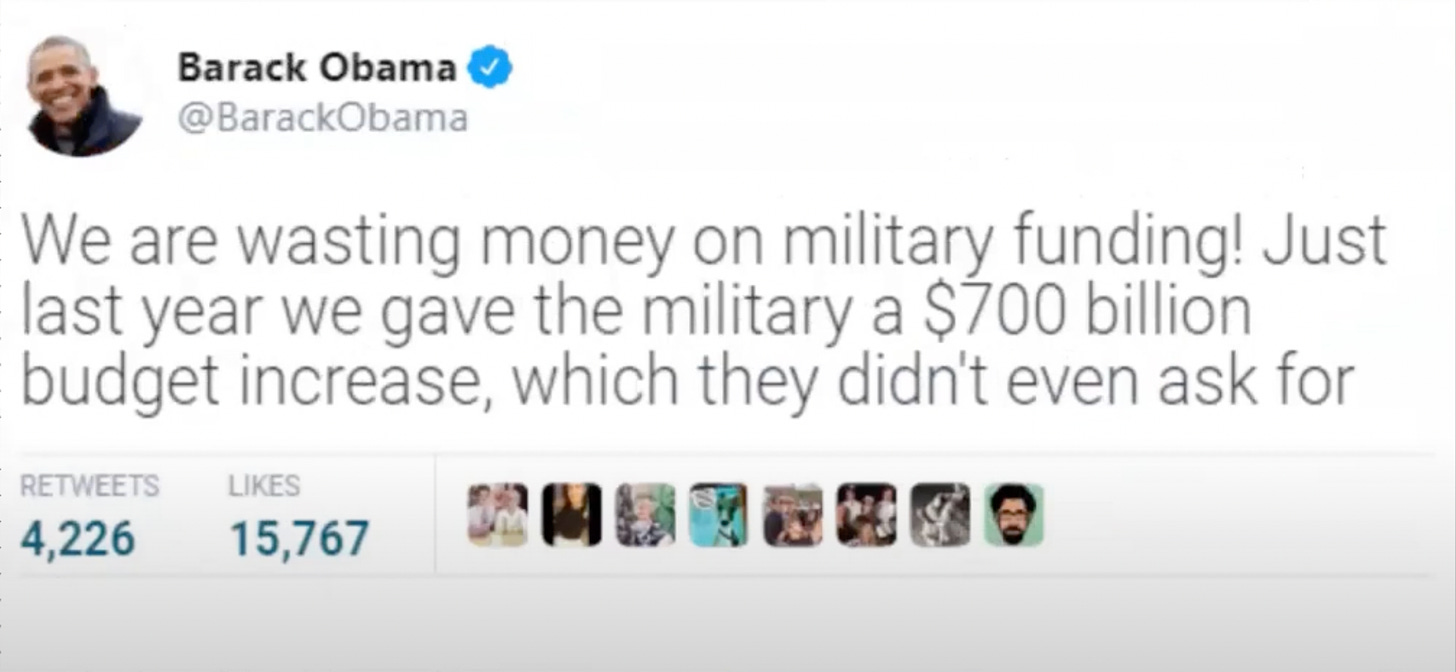

Social identification has wide-reaching impact, from voting behavior to the way we process information and update our beliefs. Elizabeth’s initial work (with Andrea Pereira and Jay) found that Democrats and Republicans are much more likely to believe negative fake news about the out-group (i.e. a Democrat is more likely to believe a negative fake news story about Republicans and vice versa). When it comes to misinformation, it is crucial for us to understand how our partisan lenses may be affecting not only our ability to discern true and fake news, but how we respond to evidence that news may be incorrect.

Belief in fake news, updating beliefs, and the backfire effect

Elizabeth’s more recent work has sought to understand precisely that. In a series of experiments, she tested how people react to corrections of fake news: do they rationally update their beliefs, fail to update, or backfire (double down on their initial belief in the information even more)? Importantly, she manipulated who the tweets and corrections came from—either a political in-group, out-group, or a neutral party—to understand the role of partisanship.

In the first experiment, participants saw a tweet with a false claim about a polarized topic from either a prominent in-group or out-group politician, and were asked how much they believed the statement. The tweet was then corrected by a member of the opposite party, and Elizabeth measured how participants’ beliefs changed in response to seeing this correction.

For each subsequent experiment, Elizabeth and her colleagues manipulated the identities of tweeters and correctors to tease apart this relationship between partisan identity, belief, and belief updating. The second study used less well-known politicians, in addition to non-partisan control sources (eg., Pew Research Center), to test the strength of invoking partisan identity, even for less prominent figures. The third experiment took this even further, using accounts made to look like average citizens with either a neutral identity (just some guy named “Matt”) or clear partisan identity (“AOC Queen” or “GodsGuns&Trump”).

Across all three experiments, she found clear partisan bias in belief of fake news, meaning participants were more likely to believe fake news when it came from their political in-group vs out-group or a neutral source. Participants also generally updated their beliefs after seeing a correction (which is good news for society!).

However, partisan bias in belief updating appeared to be a bit more complicated: this bias was only seen for Study 2, which used less prominent politicians and neutral information sources. For this experiment, participants updated their belief more when the correction came from an in-group politician or nonpartisan organization compared to an out-group politician.

The impact of our partisan identities on the way we process and respond to information was also showcased by this project’s results around backfiring: people were more likely to backfire (double-down on initial belief in the information) when initial information came from an in-group member and the correction came from an out-group member. They became even more committed to their initial belief in these cases.

To hear the rest of Elizabeth’s dissertation, including her studies analyzing the relationship between age, partisanship, and sharing of fake news, you can watch her full presentation on our Youtube channel:

And you can read the first portion of Elizabeth’s dissertation, a review chapter on the psychology and neuroscience of partisanship for the Cambridge Handbook of Political Psychology, here.

Congrats Dr. Harris!

New papers and pre-prints

Speaking of social identity, how does this shape our belief in conspiracy theories? In a new paper for Current Opinion in Psychology, Claire Robertson, Clara Pretus, Steve Rathje, Elizabeth Harris, and Jay argue that the motives behind conspiracy theory belief are often related to social identity. This view helps explain why conspiracies often spread within certain communities.

Read the paper to learn more about how conspiracy theories can fulfill social identity needs such as belongingness goals, the need to think highly of one’s in-group, and the need to feel secure in one’s group status:

Also on theme, lab members Clara Pretus, Ali Javeed, RA Diána Hughes, and Jay teamed up with Kobi Hackenburg, Manos Tsakiris, and Oscar Vilarroya to investigate the effectiveness of identity-based interventions in reducing the spread of partisan misinformation. We found that ostensibly crowdsourced accuracy judgments in the form of a ‘Misleading’ count reduced likelihood of sharing misinformation, especially when these judgements reflected an in-group’s opinion (versus general users). This intervention was much more effective than other interventions (eg., accuracy nudges). You can read the pre-print here:

We have another new pre-print from Philip Pärnamets, Mark Alfano, Robert Ross, and Jay on open-mindedness and support for public health measures. We found that during the early stages of the pandemic, open-mindedness correlated positively with adhering to physical distancing measures, maintaining physical hygiene, and supporting policy measures, while correlating negatively with believing in COVID-19 related conspiracies. You can read it here:

Our paper on cooperation is now in press at Advances in Experimental Social Psychology! You can read it here, and for a TL;DR you can check out our newsletter post from when the paper was accepted!

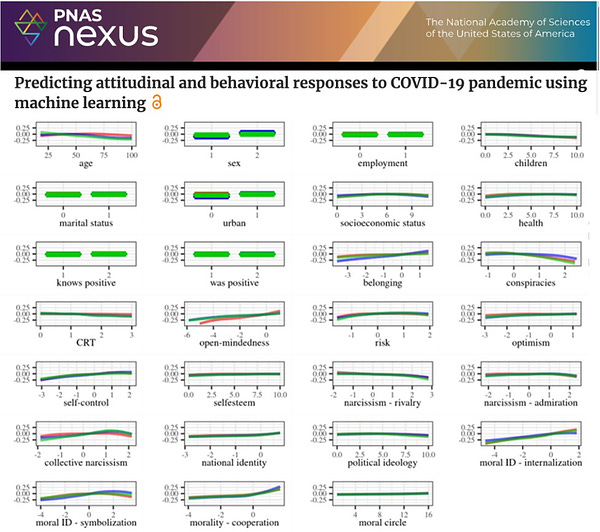

In a new paper for PNAS Nexus led by Tomislav Pavlović, Jay and many (many) other authors used machine learning on our recent global dataset to test how well constructs from social, moral, cognitive, and personality psychology, as well as socio-demographic factors, predicted attitudinal and behavioral responses to the pandemic. You can check out the open-access paper to see the full results, but the most consistent prediction was that individuals perceiving moral traits as central to their self-concept reported higher adherence to preventive measures:

New workshop

Could going viral on TikTok be good for science? Our lab’s TikTok influencer and new postdoc Steve Rathje created a workshop on how to make effective science TikToks and spoke about the importance of communicating quality science on the app. You can watch his workshop here and check him out on TikTok at @stevepsychology.

Public outreach and talks

After four years, Jay and his co-authors wrapped up their Letter to Young Scientists column for Science Magazine. Their final piece discussed how to foster healthy scientific independence, and you can check out the rest of the column—which includes advice for things ranging from how to apply to graduate school, say “no” in your professional life, to how to write a clear, compelling CV—on Science.

Our RA Shamauri Rivera presented his work in our lab at the NYU SURP Conference this month! Shamauri has spent the summer analyzing how vocal synchrony is related to the alignment of views in moral conversations.

Jay recently spoke at the Aspen Ideas Festival on a panel with Charles Duhigg and Annie Murphy Paul. He discussed the power of a shared goal and how “connectors” can influence positive change, among other topics around building smarter groups:

Jay was also recently on the Stanford Psychology podcast, where he talked about lots of research from our lab and the worst paper rejection he’s ever experienced:

The Power of Us

We are so proud to announce that Jay’s book with Dominic Packer, The Power of Us, is the winner of the prestigious 2022 APA William James Award!

This month in photos

This month’s collection is mostly highlights from Dr. Harris’ PhD defense celebration last week!

In case you missed last month’s newsletter…

As always, if you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to the Lab Manager (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com) who writes our monthly newsletter. We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

That’s all, folks—thanks for reading and we’ll see you next month!