Are humans intuitively cooperative or selfish?

We explain how neurons, norms, & institutions shape the decision to cooperate; new research on moral judgements around the world; & advice for early career scientists

Your boss calls you into her office. She says she has some news to share you with you, and she wants to let you know in person. A few minutes later, you’re told the great news: you’re getting a bonus to reward you for all of your hard work!

But there’s a slight catch—you’re not the only one in the office who got a bonus. And instead of immediately pocketing your cash, you and your colleagues each have to make a decision about what to do with it.

Your boss informs you and the 4 other bonus recipients that you must choose to either pocket your $1000 bonus, or donate any amount you’d like to the collective pool. The pool will be multiplied by 1.5, and split up evenly among the bonus recipients—meaning if everyone donated all of their bonus, each colleague would walk away with an extra $500 in cash. What would you choose to do?

This decision to act in your own self interest vs. the collective interest is at the heart of cooperation. From fostering organizational success to addressing climate change, we need to understand what drives people to work together—and what pushes them apart.

These questions have wracked the minds of philosophers for centuries, and more recently, scientists have delved into the psychological processes behind cooperative decision-making. Some have speculated that is it our human instinct towards cooperation—an intuition to work together with others. Others have claimed we must deliberately override the deep rooted human instinct to act on our selfish impulses.

In our latest review paper, recently accepted at Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, we argue that neither of these arguments is quite right. To determine the chances that people might cooperate (or defect) we would ask different questions altogether, such as: What are the rewards for cooperating (as seen in the Dilbert cartoon we posted above)? Are you part of a tight knit team? What kinds of norms around generosity already exist in your group? Have you cooperated in the past? And do you think that Angela from accounting, who took your last yogurt from the fridge last week, will be a trustworthy contributor to the bonus pool?

In our view, the decision to cooperate must be understood by studying the influence of a complex array of cognitive, social, and institutional factors. Our paper proposes a more comprehensive approach: a value-based framework for understanding cooperation.

In other words, when people decide whether or not to cooperate, a variety of mental processes feed into calculations of value—taking into account a decision’s outcomes (to the self and others), those outcomes’ probability, and one’s social preferences (concern for own and others’ self-interests). This evaluation process can help us understand how both psychological factors (e.g., prosocial tendencies, social identities) and environmental or contextual factors (e.g., social norms, societal institutions) affect cooperative decisions.

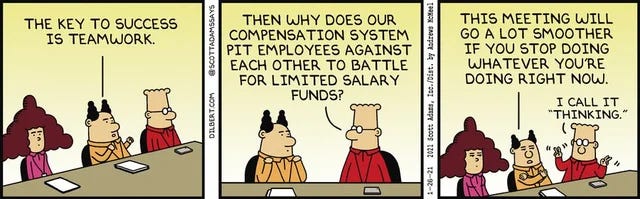

At the neuro-cognitive level, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) acts as a neural integration hub for our cooperative decision-making system. It receives inputs from various brain areas and processes that have an impact on our cooperative decisions, such as our goals, self control, attention, learning, memory, and the representation of others’ minds. For example, manipulating attention can alter the weights given to self and other related outcomes, and activity in the memory system has been found to support adaptive social decision-making based on past encounters with social partners.

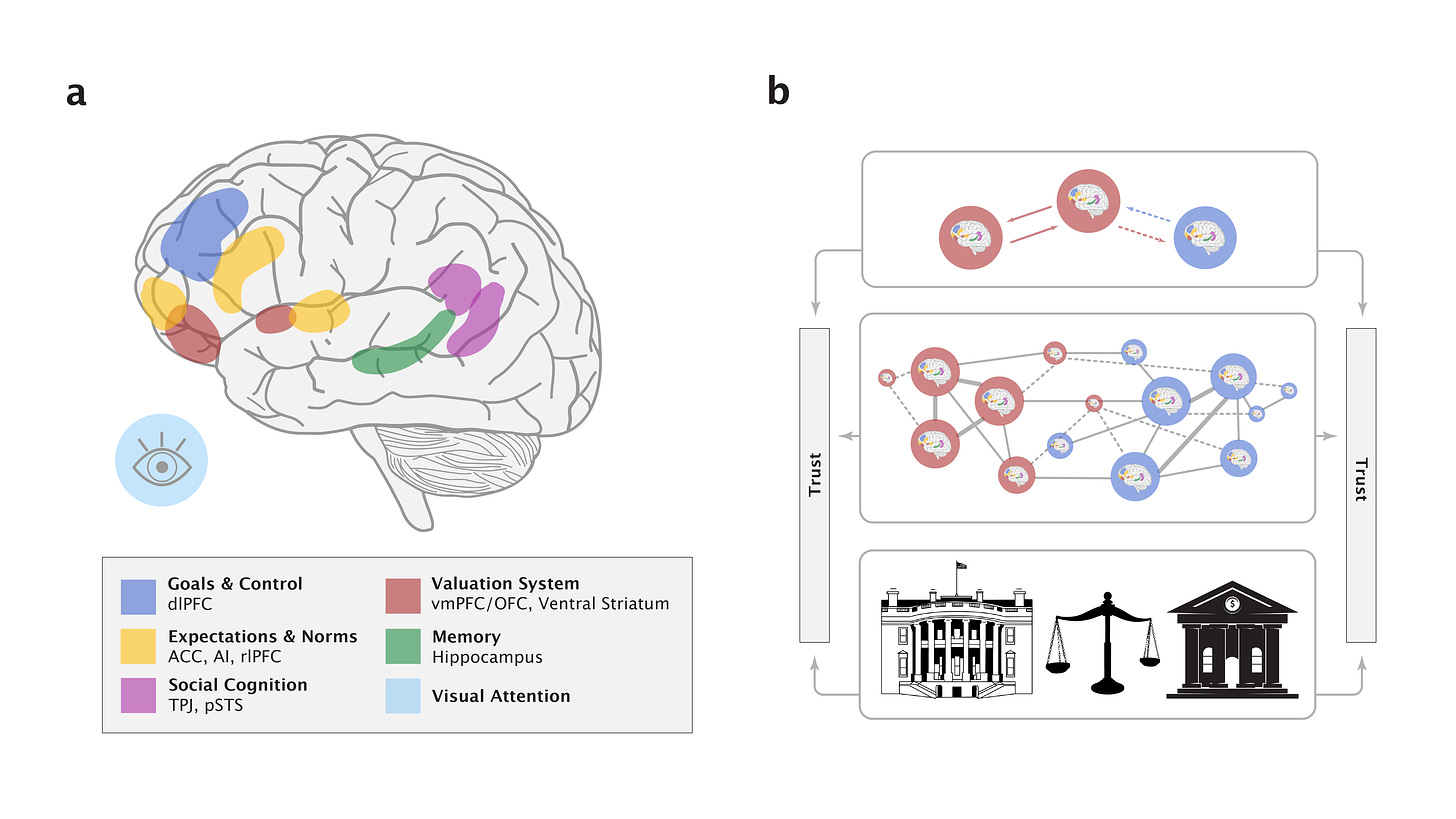

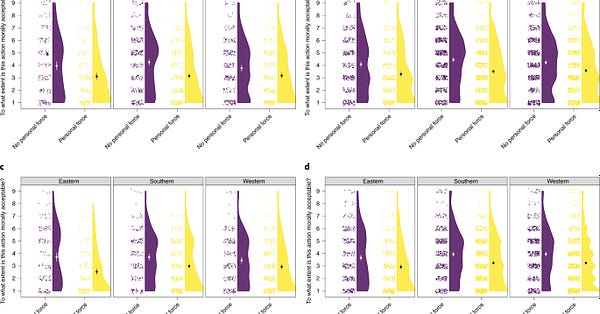

Our social reality—for example, norms, our group identities, and our social networks—also shapes how, when, and why we decide to cooperate. Group norms play a powerful role in determining both cooperation and responses to non-cooperators, and norms of cooperation can be quite varied across cultures (see figure below). People cooperate more with in-group than out-group targets, and making shared group identities salient can play a powerful role in inducing cooperation. Social networks also play a role in cooperation, as influences can spread through a network and impact (either directly or indirectly) whether other people choose to cooperate.

But we can’t understand the choice to cooperate without also examining the role of institutions or institution like-structures, which can affect multiple inputs to a decision maker’s value calculations. Institutions, when they function well, can be important productions of trust, and they have been shown to increase cooperation between out-group members, have been associated with negative correlations for in-group favoritism, and can reduce intergroup bias. By providing a sense of security, or top-down incentives like accountability and enforcement, institutions can significantly increase cooperation between individuals and groups.

So, would you choose to pocket your bonus, or donate some or all of it to the pool? Whatever you choose, we argue that it is not grounded in an overarching human instinct towards selfishness or cooperation. Rather, your decision is a value calculation taking into account the wide range of inputs in our highly complex world—from neurons to norms to the institutions in our society.

To get a sneak peak at the full paper before it appears in print, and to dive into the research behind our framework, you can read the full paper (by Jay, former postdoc Philip Pärnamets, lab affiliate Diego Reinero, and Dominic Packer) on PsyArXiv. Stay tuned for when the article is published later this year!

And if you want to know a little more about the human side of collaborations like this, check out this thread from Diego (he starts by capturing our own cooperative research process in action!):

More new papers

Our former PhD student Diego Reinero recently had a paper published in Nature Human Behavior! The paper (which was led by Bence Bago and had over 270 authors) explored how psychological and situational factors (for example, the intent of the agent or the presence of physical contact between the agent and the victim) affect moral judgments in 45 different countries. Their results suggested a culturally universal finding: when personal force is seen to be necessary to save more lives, people are less likely to favorably judge a consequentialist outcome (an outcome that saves more people). You can read the full paper here.

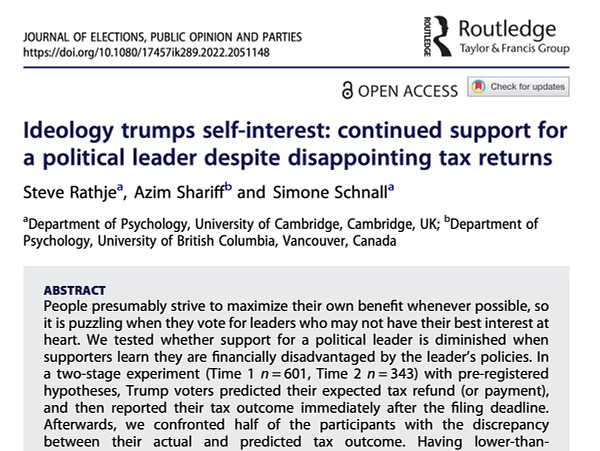

Incoming postdoc Steve Rathje (with Azim Shariff and Simone Schnall) recently published a paper in Journal of Elections, Public Opinions, and Parties! The paper tested whether support for a political leader is diminished when supporters learn they are financially disadvantaged by the leader’s policies, and found that when participants received lower-than-expected tax outcomes, it was not associated with reduced support for former President Donald Trump—either on its own, or in combination with being reminded of this outcome. You can read the full paper here.

While this isn’t a paper from the lab per se, this new paper published in Games summarizes the key insights for economics from The Power of Us:

“This book challenges the idea that social identity and ingroup bias are ineradicable. For economists, it also succeeds in explaining when and why “leveraging the collective mind” can be an effective way to affect behavior, sometimes even more effective than providing monetary incentives, thus enlarging the set of tools that economists are familiar with and advocating for a deeper comprehension of how social identity can be built but also dismantled.”

Public outreach

Jay gave a talk about “The Power of Us” in the virtual world at the Paradigm Shift conference in Brooklyn this month! His talk explored how to harness shared identities to build great teams:

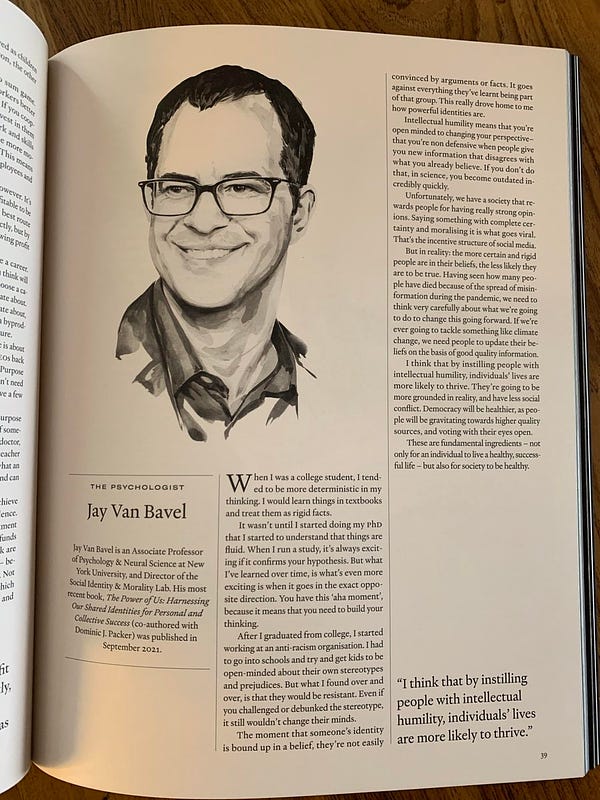

Jay was interviewed for Wealth Magazine about how to understand and harness social identity for good and overcome our biases and blindspots:

Jay was interviewed for The Beautiful Truth magazine about the importance of intellectual humility (fun fact: intellectual humility is also important to the functioning of healthy ant colonies!) You can watch a video of his interview here.

Advice corner

A lot of great advice for early career researchers has been circulating online recently, and we thought we’d share a few pieces in case they are helpful to anyone!

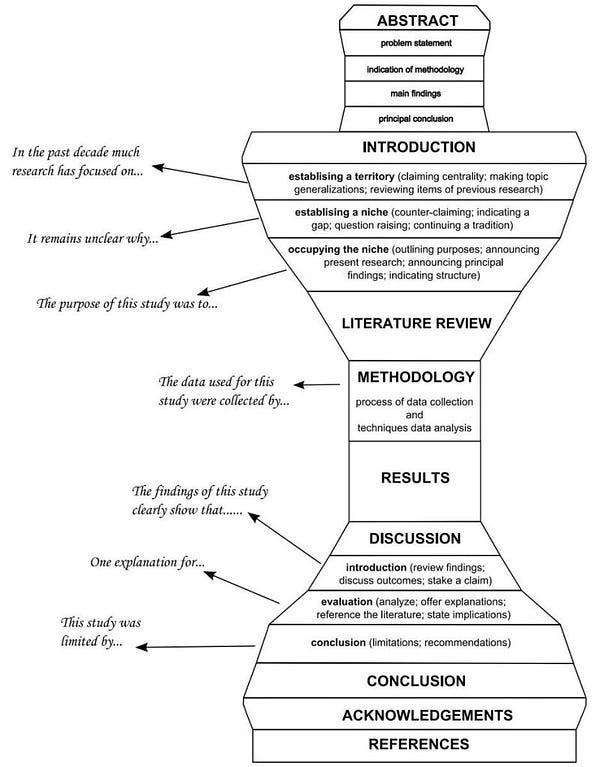

Writing a paper can often feel like a daunting undertaking for new researchers. This handbook from the Asian Institute for Technology provides some tips for breaking down the writing process:

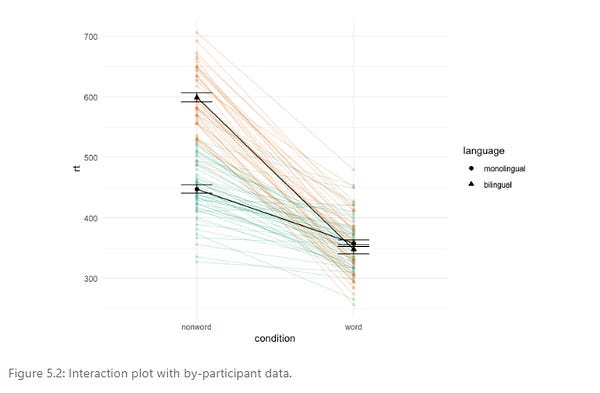

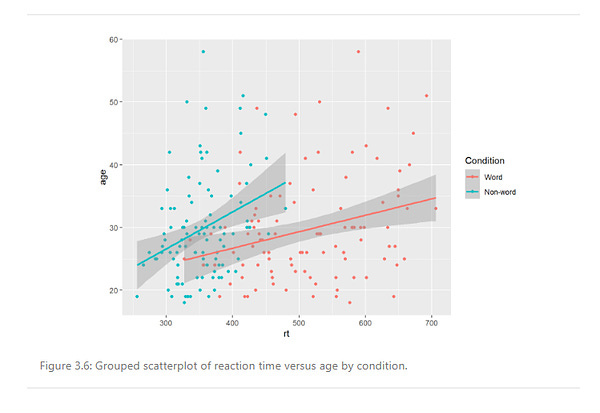

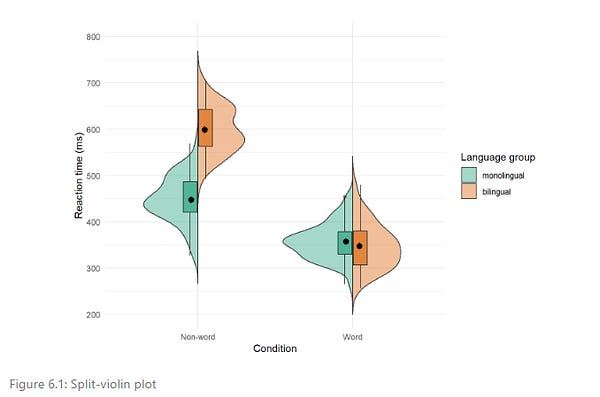

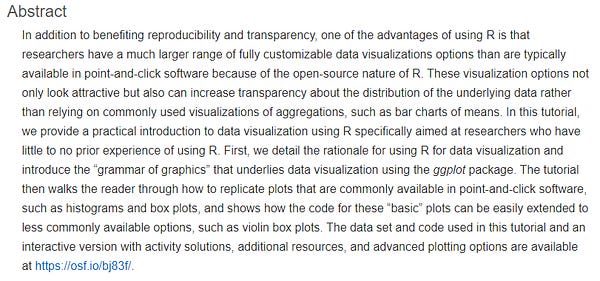

New to R? Check out this paper about data visualizations, written specifically for those who don’t use R:

And finally, our former PhD student Billy Brady was named one of the APS Early Career Award winners interviewed for this piece highlighting advice for junior psychologists:

Lab member shoutouts

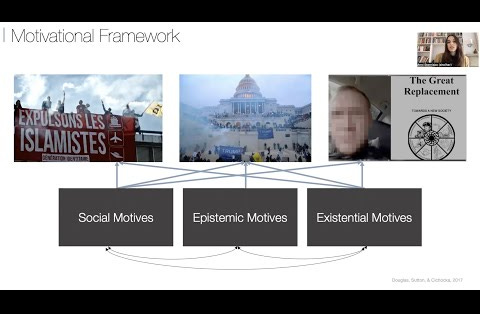

Dr. Anni Sternisko, our lab’s newest PhD, won the 2022 Douglas H. and Katharine Fryer Thesis Award for Best Doctoral Thesis!

Lab affiliate Rachel Leshin won two department awards — the Friends of Katzell Summer Fellowship for Applied Research and the Coons Graduate Student Travel Award!

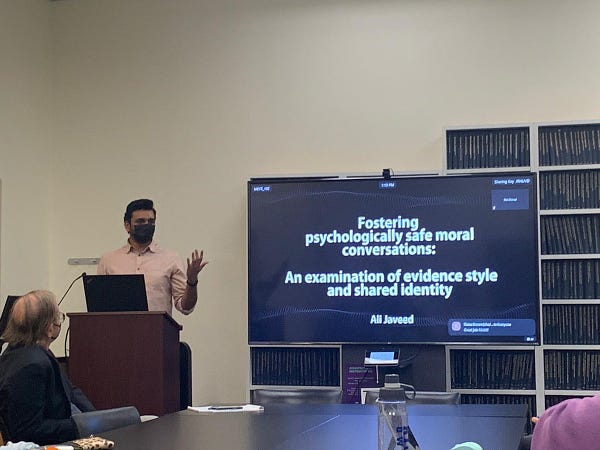

PhD student Ali Javeed gave his first Brown Bag talk for the Social Psychology program this month, presenting a novel application of psychological safety to ease moral-political conversations:

Research assistant Yara Kyrychenko is off to Cambridge this fall (and as a Gates Scholar, to boot) to get her PhD in social psychology! She’ll be working with Sander van der Linden and Jon Roozenbeek on social identity and misinformation:

Research assistant Anastasiia Korolevskaia was accepted into the NYU Honors Psychology program to work with Lawrence Ian Reed.

And finally, our research assistant Armon Dadvand received funding from the Dean’s Undergraduate Research Fund, and was also named this year’s Arthur Noulas Research Scholar based on the strength of his proposal!

Lots of wonderful news to celebrate!

This month in photos

Lots of April birthdays (lab members Diego, Steve, and Clara) calls for lots of birthday hats! We’ve had fun celebrating with our new fave accessories (and looking like gnomes in the process):

We had a welcome party for our newest visiting researcher Anna Greenburgh (bottom left), who is with us for a few months from University College London! Anna studies how paranoia spreads in group online contexts. Stay tuned to hear more about her work:

In case you missed last month’s newsletter…

Thanks to Katie Brown for drafting the lab newsletter! As always, if you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to Katie (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com). We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

That’s all, folks—thanks for reading and we’ll see you next month!