Morality in the Anthropocene

How our ancient moral instincts drive outrage and animosity on the internet

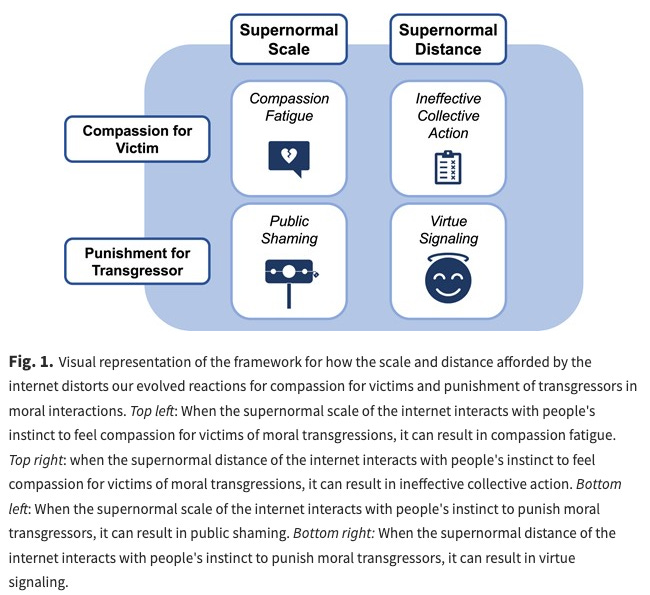

Just as the atomic bomb drastically changed modern warfare, the internet has made a profound impact on moral psychology. Humans have an innate tendency to care about moral issues like fairness, empathy, and reciprocity, all traits that were evolutionarily adaptive for small, closely knit groups to survive. However, the internet connects over 5 billion people together in a brand new, technological environment that has fundamentally altered our social world. In our latest paper, we argue that the moral instincts humans developed in small social networks are poorly suited for this large, interconnected environment due to the scale of the internet and the distance between people on the internet (see Figure 1 below). We explain the profound consequences this has had on our moral judgment and collective behavior.

The Evolutionary Underpinnings of Moral Cognition

Humans evolved as a highly social species, with much of our innate behavior geared towards navigating social situations and ensuring group cohesion. Early humans developed moral instincts to facilitate cooperation and minimize conflicts within their communities. Violations of cooperative norms, such as causing harm, failing to reciprocate, or betraying group obligations, are seen as morally transgressive and elicited quick, negative reactions. These responses helped build stronger, more successful groups over time by promoting helpful and protective behavior, and reducing in-group violence. As society became more complex over time, so did humans’ moral reasoning, which relies on complex cognitive systems and cultural norms and contextual cues.

The Internet and Supernormal Moral Stimuli

The internet has drastically changed the scale of social interactions and information dissemination. Unlike earlier technologies like the telephone or mass media, which connected people one-to-one or one-to-many, the internet allows for many-to-many connections without concern for time or distance. This unprecedented connectivity has led to an overabundance of moral content online, far surpassing what people encounter in their offline lives or through traditional media (TV, radio, and newspapers).

Online platforms also exploit humans' attentional preference for morally relevant stimuli. Moral content also captures attention and generates high engagement, leading to frequent sharing and visibility. In turn, this overabundance can have important cognitive consequences, like people perceiving moral transgressions where there aren’t any, or biasing people’s moral evaluations towards negativity.

The moral content that people are exposed to online is also more extreme than typical moral content, similar to supernormal stimuli. Supernormal stimuli mimic the environmental stimuli that we tend to preferentially attend to, but are more extreme than they would ever be in the natural environment. As a result, moral content online may capture our attention more strongly, and trigger unhealthy behavior in spite of our intentions.

This combination of the extremity and overabundance of moral content online creates a cyclical process where algorithms aiming to maximize engagement on social media “learn” that the most extreme content is the most successful at garnering online engagement, and prioritize that type of content. We argue that two of the resulting consequences are the disruption of compassion and 3rd party punishment online.

Compassion and Empathy

Compassion and empathy evolved to foster cooperation and care within groups. However, it is also a limited cognitive resource and in an online context, empathy is strained by the vast number of victims and the distant nature of social connections. The internet exposes individuals to an unprecedented scale of suffering, which can lead to emotional numbness and reduced prosocial behavior. When people are overloaded with requests for empathy, people find assigning blame easier than having empathy.

Since social media is overloaded with such stimuli, this may lead to people assigning blame more often, rather than empathizing with a victim in response to moral transgressions. People may also grow increasingly numb to the endless suffering they see on social media. Online empathy is often weaker than offline empathy, and low-cost actions like "liking" or "sharing" can create a false sense of moral action due to moral licensing, reducing genuine efforts to help. This can weaken collective efforts at organizing as well, since people can get social credit for supporting a cause without making genuine change.

Witnessing moral transgressions spurs a desire to punish wrongdoers, a behavior that is deeply rooted in human evolution. In small groups, third-party punishment helped deter cheating and fostered group cohesion. However, online, the scale and anonymity of interactions change the dynamics. The internet allows for massive, often disproportionate, public shaming, where thousands can target a single individual without personal stakes. This can incentivize virtue signaling, where people engage in moral grandstanding to enhance their social image rather than effecting real change.

Supernormal Distance and Ineffective Collective Action

The physical and psychological distance between online users undermines the traditional functions of punishment and collective action. Online shaming and punishment are rarely costly to the punisher, making them ineffective signals of group commitment. This leads to superficial signaling and can reduce the perceived sincerity of moral outrage. Additionally, online activism often results in broad but shallow engagement, which may raise awareness but fails to drive meaningful, lasting policy changes.

To mitigate these issues, future research should focus on developing interventions that reduce negative outcomes related to online compassion and punishment. Researchers need greater access to social media algorithms to understand their impact on behavior and emotion. Collaborative efforts across cultures are also essential to test evolutionary hypotheses and develop effective strategies.

Mass sharing on the internet can be helpful. For example, social media has been credited with facilitating demonstrations of collective action around the globe such as the Arab Spring, MeToo, and Black Lives Matter. The internet has brought unprecedented connectivity and access to information, but it also challenges our evolved moral instincts in ways that can be harmful to individuals and society.

Understanding these challenges is crucial for navigating and shaping the online environment to prevent maladaptive outcomes. While the internet offers many benefits and has been used as a tool for collective organizing and platforming disenfranchised voices, its structure and incentives currently exploit our moral instincts, leading to negative consequences that should be addressed through thoughtful design and regulation.

FULL ARTICLE: Claire E Robertson, Azim Shariff, Jay J Van Bavel, Morality in the anthropocene: The perversion of compassion and punishment in the online world, PNAS Nexus, Volume 3, Issue 6, June 2024, pgae193, https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae193

This summary of the article was edited by Sarah Mughal and Jay Van Bavel.

Video & Audio Spotlight

Jay recently gave a talk on “The science of misinformation and what we can do about it” at the United Nation’s Division for Inclusive Social Development webinar. You can watch a recording of his talk here.

Events

We are excited to announce that lab member Steve Rathje just won a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship Award for his research examining the causal impact of social media on our attitudes, beliefs, and well-being!

Our lab hosted an interactive history event with Greg Trefry from VOXPOP. VOXPOP bring civics and history to life in the classroom using media-rich, collaborative, role-playing experiences. We are planning a collaboration to see how these role-playing experiences impact interpersonal and intergroup relations in the classroom. To see how it works, we simulated Shay’s Rebellion at a lab meeting. Tons of fun. Highly recommended!

Jay and Jon Freeman recently organized a joint picnic with NYU and Columbia’s Psychology Departments at Central Park. Thanks to everyone who joined us!

If you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to our Lab Manager Sarah (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com) who puts together our monthly newsletter. We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

And in case you missed it, here’s our last newsletter:

That’s all for this month, folks- take care, and we’ll see you next month!

I don’t have a post but read this https://medium.com/@ingvargrijs/versions-of-the-moral-29cf89a13fdb

Fascinating article I’ve been thinking along similar lines so appreciate this work and references.

I may well reference this article for context for a post about how AI fits into this (my area)