Election Edition: How political identity affects what we believe

Why social identity shapes our susceptibility to misinformation

With the US Presidential Election on the horizon, most people we know are anxiously checking polls, doomscrolling the news, and debating politics with their friends and families. One of the most uncomfortable parts of this experiences is when we come to a disagreement with someone from a different political party—it is often the case that we disagree about basic facts.

This turn of events feels particularly disturbing because it often violates the norms of healthy political discourse. As former New York Senator, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, once said “You are entitled to your opinion. But you are not entitled to your own facts.” When someone invokes Pizzagate or stop the steal, they might as well be talking about Bigfoot, chemtrails, or UFO abuctions. It puts an immediate halt to any semblance of a rational debate. So why does it feel like so many people have gone in this direction?

Our paper, “Updating the identity-based model of belief: From false belief to the spread of misinformation”, explains how and why people’s social identities influence what they believe—even when it’s factual wrong. In this article, we explain how misinformation spreads and how partisanship—our identification with political parties—can distort our understanding of the world. People's social identity plays a crucial role in shaping our beliefs and makes us more likely to believe or share false information when it makes our group look good (or, more frequently, when it makes our opponents look bad).

Partisanship extends beyond agreeing with one’s party’s policies and views; it also encompasses people’s sense self-concept. Being a member of a political party can become a central part of people’s identities. Just like people are motivated to see themselves in a positive light, they are also motivated to hold their group (e.g., political party or favorite leader) in high regards.

Sometimes, the motivation to be part of a valuable group (such as social identity goals) is at odds with other goals such as the goal to accurately represent the world (such as accuracy goals). For example, social media users might repost misleading or inaccurate posts to get engagement and approval from their like-minded followers.

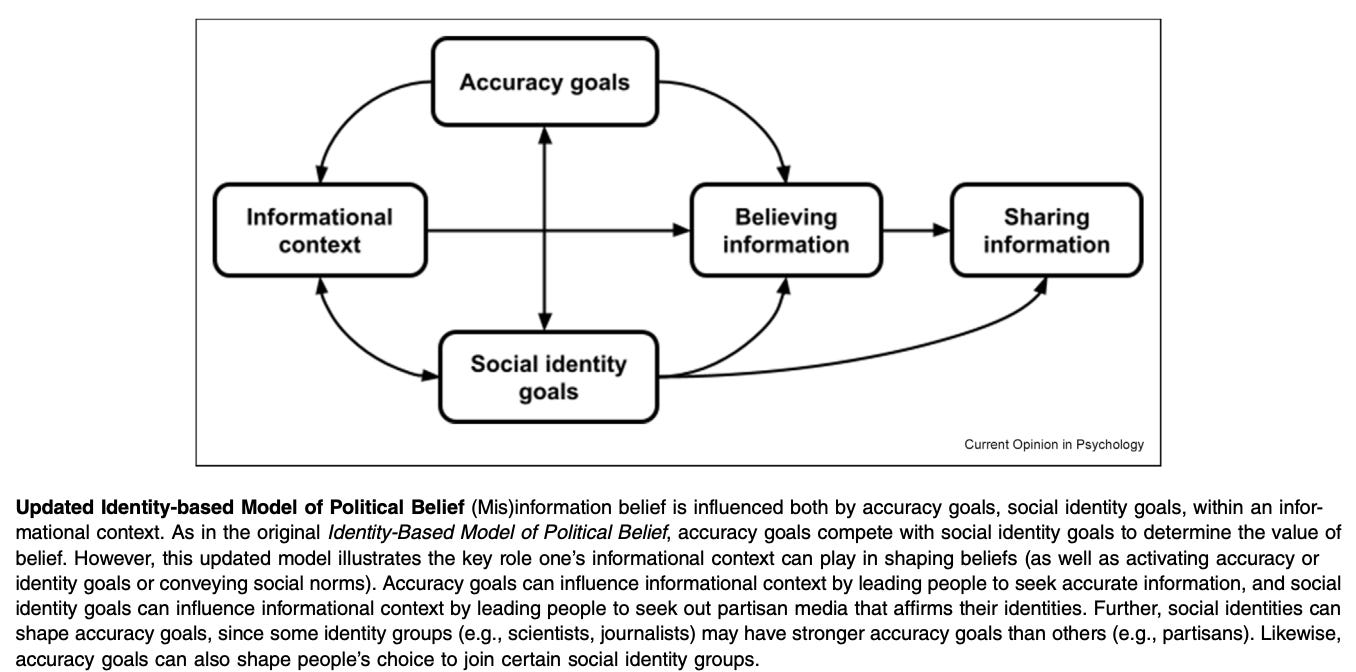

Our Identity-Based Model of Political Belief explains how the push and pull between social identity goals and accuracy goals shapes people’s political beliefs, (biased) information processing, and sharing of (mis)information. According to this model, social identity goals can override accuracy goals, and vice versa. Most people value accuracy much of the time. But when people prioritize social ties and belongingness to their party over accuracy, they align their beliefs with other party members rather than facts.

In the context of (mis)information, this means that people might ignore factual information if it threatens their positive partisan identity, emphasizing flattering and validating information instead. In lieu of accuracy concerns, people might believe or share false information simply because it reinforces their positive beliefs about their party, or they want to signal their party loyalty. For example, many supporters of Donald Trump believed and spread false claims about the 2020 presidential election because it helped satisfy their need for belonging and sense of superiority, although the facts said otherwise.

Group norms also affect the spread of misinformation. If groups tolerate, validate, or even encourage the spread of dubious and false information, motivation for fact-checking or correction is low. On the other hand, groups that uphold norms of rigorous fact checking, like scientists, are much less likely to spread and be susceptible to misinformation.

Taken together, the model proposes that misinformation can serve a multitude of social goals, like belongingness and group signaling, rather than purely informational functions, and can reinforce group norms on information sharing. This is why simply providing factual corrections to misinformation doesn’t always work well (although it tends to be highly effective in non-partisan contexts). For instance, research finds that fact checks tend to be least effective on highly polarized issues—precisely where identity needs outweigh accuracy needs.

We recently fleshed out the Identity-Based Model of Political Belief model to account for the critical role of informational context in political beliefs and misinformation. Motivated cognition cannot fully explain partisan differences in belief. Partisan differences can also arise, for example, because people are exposed to different information sources. Thus, beliefs and values both play an important role in guiding belief formation and updating.

Our extended model outlines not only how our beliefs are directly shaped by accuracy and social goals, but also how they’re indirectly shaped through selective exposure to information. We may actively seek out news sources that are popular within our party and validate our pre-existing beliefs, and may only deem those particular news sources as trustworthy; although such selective exposure does not always have to be intentional and motivated. Changing or diversifying people’s news sources might therefore be on way to shift people’s beliefs and might be an opportunity to establish common ground between opposing parties.

This article summary was generated by ChatGPT and edited by Sarah Mughal, Anni Sternisko and Jay Van Bavel.

Citation: Van Bavel, J. J., Rathje, S., Vlasceanu, M., & Pretus, C. (2024). Updating the identity-based model of belief: From false belief to the spread of misinformation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 56, 101787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101787

A/V Spotlight

On the issue of false beliefs, check out this clip of Jay speaking on a panel at this year’s APA conference! He discusses factors that facilitate the spread of misinformation, and what to do about it. Watch it here.

New Preprints and Papers

Our paper “People Think That Social Media Platforms DO (but Should Not) Amplify Divisive Content” was officially published in Psychological Science! We find that people report seeing divisive, misleading, and negative content go viral, but that they don’t that type of content to go viral; rather, they want positive, educational content to be what they see on social media. This paper was led by Steve Rathje, Claire Robertson, Billy Brady, and Jay Van Bavel. You can read it here.

Rathje, S., Robertson, C., Brady, W. J., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2024). People Think That Social Media Platforms Do (but Should Not) Amplify Divisive Content. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 19(5), 781-795.

We also have a new paper analyzing the impact of political polarization on the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. We conclude that a large part of the death toll of COVID-19 was preventable and due to the polarization of the pandemic. We also discuss public policy changes that can be made to avoid these mistakes in future public health crises. This paper was led by Jay Van Bavel, Clara Pretus, Steve Rathje, Philip Parnamets, Madalina Vlasceanu, and Eric Knowles. You can read it here.

Van Bavel, J. J., Pretus, C., Rathje, S., Pärnamets, P., Vlasceanu, M., & Knowles, E. D. (2024). The Costs of Polarizing a Pandemic: Antecedents, Consequences, and Lessons. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 19(4), 624-639.

We also had a paper accepted to Current Opinion in Psychology! “Inside the Funhouse Mirror Factory: How Social Media Distorts Perceptions of Norms” reviews the evidence behind how social media presents a biased view of social norms, and the consequences thereof. You can read a preprint here.

Our postdoc Steve Rathje also recently published a new correspondence in Nature, where he argues in favor of regulations to allow researchers access to social media data from big tech companies. You can read it here.

News and Updates

On October 3rd, Jay will be giving a talk at Vanderbilt Law School about using psychology to combat climate change polarization! Stop by if you’re in the area:

Jay is also giving a talk for the Montessori School of Denver on the Power of Us- you can reserve a free spot at the talk here if you’re in the area!

Jay was recently a guest on the podcast “The Connection”, where he talked about the benefits—and consequences—of being part of a social group. You can listen to the episode here.

Jay was also a guest on the “Work Life with Adam Grant” podcast, where he discussed our lab’s research the science of virality and how people can find common ground around more uplifting content. You can listen to the podcast here.

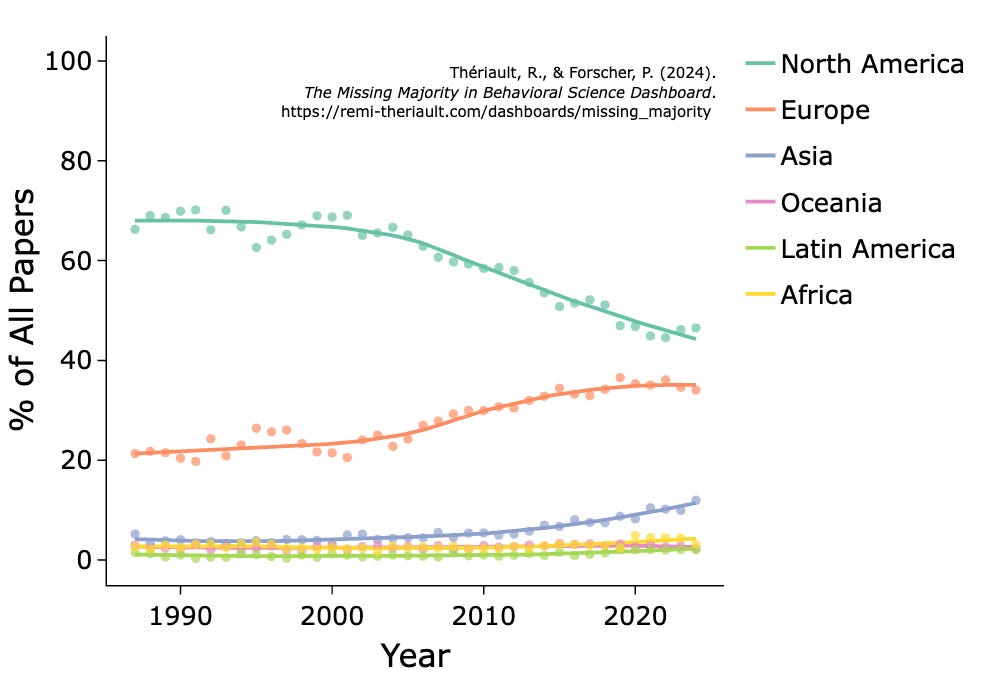

Behavioral science aims to understand and improve the behavior of all humans, yet the Global South remains vastly underrepresented in both participant samples and researchers. This oversight may results in a skewed understanding of behavior. To address this disparity, incoming postdoctoral fellow Rémi Thériault helped develop the Missing Majority Dashboard, which tracks the representation of the lead authors on behavioral science papers from the Global South in 51 behavioral science journals. For more information, please refer to the press release or visit the dashboard directly.

If you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to our Lab Manager Sarah (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com) who puts together our monthly newsletter. We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

And in case you missed it, here’s our last newsletter:

That’s all for this week, folks - take care, and we’ll see you next month!