Why we mis-predict the future: The best-case heuristic

Our latest paper explains why people mis-predict the future across a wide range of topics.

When thinking about romantic relationships, personal health or politics, people can imagine a broad range of alternative futures. But how do we generate our most realistic scenario? A new paper by Hallgeir Sjåstad and Jay Van Bavel finds that people rely on their best-case scenario when they try to make seem realistic predictions.

Thinking in Scenarios

When facing future uncertainty in life, people must rely on predictions to make a decision. Ranging from personal health, social relationships and politics, we frequently ask ourselves the following question: “What is the most realistic scenario?” In a series of four experiments with almost 3,000 American participants, we compared how people make future predictions in different alternative scenarios.

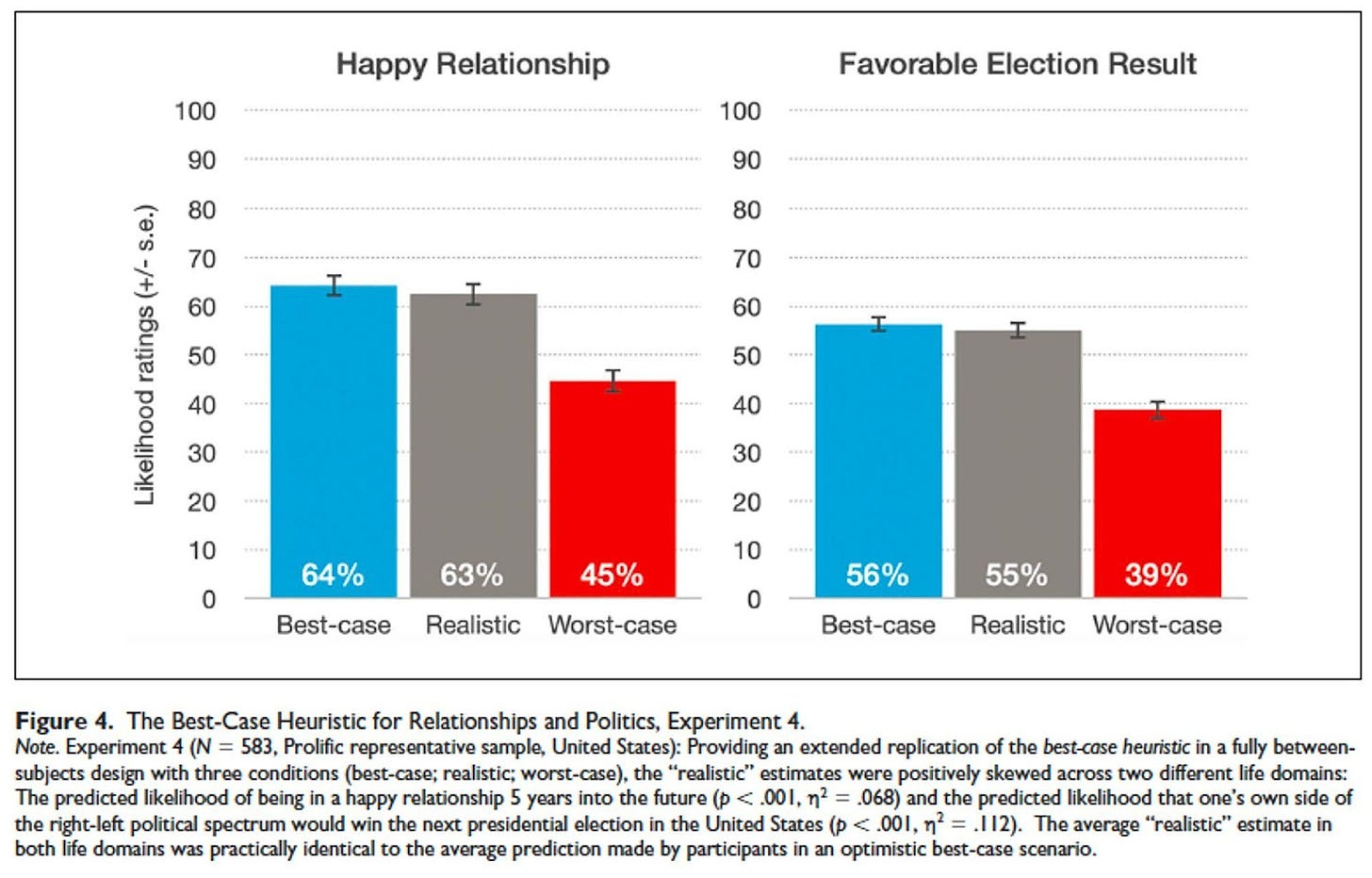

In our final experiment, participants were randomly assigned to make their predictions in one of three different conditions: 1) an optimistic best-case scenario, 2) the most realistic scenario, or 3) a pessimistic worst-case scenario. The prediction questions asked participants about how likely they thought it was that they would be in a happy relationship 5 years into the future, and how likely they thought it was that a candidate from their own side of right-left political spectrum would win the 2024 presidential election in the United States. During the first stage of the Covid-19 pandemic, they also predicted how likely it was that they would get infected by the end of the year, and how low it would take to develop a publicly available vaccine.

Aiming for the middle?

According to previous research, one effective way to improve one’s accuracy when facing future uncertainty, is to aim for the middle across multiple estimates, relying on a simple averaging strategy. In a belief survey that we collected for our paper, a majority of the participants seemed to agree with this advice, as they reported that a “reasonable person” who wanted to be as accurate and realistic as possible, would typically aim for the mid-value between their best-case and worst-case scenarios.

However, it turns out that is not how they actually generated predictions.

Leaning towards the best-case scenario

In contrast to this common advice, when people were randomly assigned to make their own predictions in just one out of three scenarios in the experiment, we found a striking pattern: People asked to make their most realistic predictions leaned heavily towards an optimistic best-case scenario. They saw the future through rose colored glasses.

In fact, the average prediction made by people in the “realistic” condition was statistically indistinguishable from the average prediction made by people who had made a similar prediction in what they considered their best-case scenario for the future (see figure below).

That is, people are making what they consider “realistic” predictions as if they are predicting a best-case scenario, reflecting what Daniel Kahneman has called “attribute substitution”. Follow-up analyses using response times, suggest that the realistic scenario predictions are leaning heavily towards the best-case scenario because what people want to happen comes first to mind. In that way, people can simplify the very complicated judgment of what is most likely to happen in reality, by relying on a best-case heuristic instead.

Political identity

In the domain of Covid predictions, we found that right-leaning conservatives thought they were less likely to become infected by the virus than left-leaning liberals, both for themselves and the average person. A majority of our American participants supported early-stage public health policies, such as physical distancing and temporary lockdown during the spring of 2020 (before the vaccines were available).

Providing some understanding of the minority who were opposed to early-stage public-health intervention, our data suggests that a combination of low-risk perception, right-leaning political views, and belief in national superiority was part of the explanation.

Despite the connection between political orientation and the general level of perceived risk, however, the best-case prediction heuristic appeared to be symmetric across the right-left political spectrum.

Our research suggest that people generate “realistic” predictions by leaning towards their best-case scenario and largely ignoring their worst-case scenario.

Our paper was published in Personality and Social Psychology (here). To read a free pre-print of paper: https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/pcj4f/

New Papers and Preprints

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

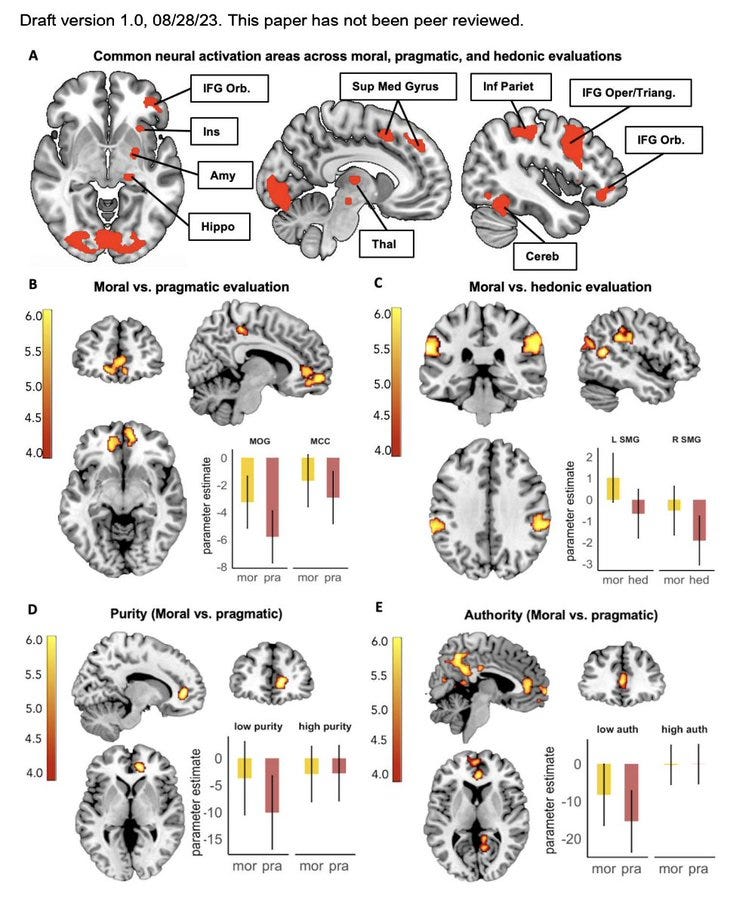

In our new pre-print, moral, pragmatic, and hedonic evaluations of whether something is good or bad rely on similar brain regions, but each type also recruits additional brain areas to make judgements. We also find that people judge the exact same action very different if they are judging it through a moral, pragmatic or hedonic lens. So be careful which lens you use! You can read the paper here: https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/esby8/

News & Announcements

This month we’d like to feature another post-doc who will be joining us next year, Raunak Pillai! Raunak Pillai is an incoming postdoctoral researcher. He received his BA in Neuroscience in 2019 from Vanderbilt University and will receive his PhD in Psychological Sciences from Vanderbilt in 2024, working with Dr. Lisa Fazio. His research aims to understand why people believe and share misinformation and identify optimal ways to deliver corrections. In grad school, he focused on the cognitive processes (i.e., memory, decision-making, language processing) involved in these issues. At the Social Identity and Morality Lab, he will continue examining these questions by integrating perspectives from cognitive and social psychology. Outside the lab, he enjoys cooking, tennis, and playing the guitar. Please join us in welcoming Raunak to the lab!

Our former PhD student Elizabeth Harris has just started a new position as a researcher at the ARTT project fighting misinformation. Her team is working on developing a Web-based software assistant that provides a framework of possible responses for everyday conversations around tricky topics. Elizabeth is working on learning more about what aspects of the tool are most helpful to users and how to best measure that the tool does its job well. While social media platforms are optimized for simple exchanges, some topics are nuanced and complicated, and require strong communications skills to respond effectively. It’s important to help people build trust online and help users answer the question: “What can I say and how do I say it?” She is helping the team understand how the tool can do the most good and use this information to help guide its design. If anyone wants more information about the project, or is interested in getting involved, please email her at elizabeth@hackshackers.com.

Our Master’s student, Ke Fang, received a $1500 grant from the Gallatin School of Individualized Study to support his thesis research this month. Ke’s thesis centers on how extremist speech online exacerbates polarization through overestimation of group norms. Congratulations, Ke!

If you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to our Lab Manager Sarah (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com) who puts together our monthly newsletter. We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

In case you missed it, here’s last month’s newsletter:

That’s all for this month, folks- thank you for reading, and we’ll see you next month!