The psychology of hate

Our latest research finds that morality is a key ingredient that distinguishes people’s conceptualizations of hate and dislike.

Hatred and dislike have been historically thought of as two highly related concepts. For instance, Darwin argued that “Dislike easily rises into hatred”, suggesting that hate is an extreme form of dislike. Even modern psychologists believe that hatred and dislike share some commonalities because they are both connected to negative feelings and influence our thoughts and actions in a similar way.

Cartoon from imgflip: hate is a powerful word

However, throughout history hatred seems to underlie violent crimes and even genocide. This extreme reaction doesn’t usually happen for things we merely dislike. Why?

Some authors believe that hatred is composed of emotions connected to morality such as contempt, anger, and disgust—and these moral emotions might underlie these extreme behaviors. Thus, the differences between hate and dislike may be due to the moral dimension of hate.

Our research team (Clara Pretus, Jennifer Ray, Yael Granot, William Cunningham, and Jay Van Bavel) tested these two complementary hypotheses: that hatred and dislike are different in terms of their degree of negativity (the intensity hypothesis), and that they are different in terms of morality (the morality hypothesis).

We tested these hypotheses in three lab studies in Canada and the U.S. We asked participants to recall things they disliked and things they hated. Participants then reported how negatively they felt towards these things and how connected they were to their moral beliefs. In a fourth study, we analyzed the language on websites belonging to real American hate groups (where people express hate) and complaint forums (where people express dislike) to evaluate differences in the use of words related to negative emotions and morality.

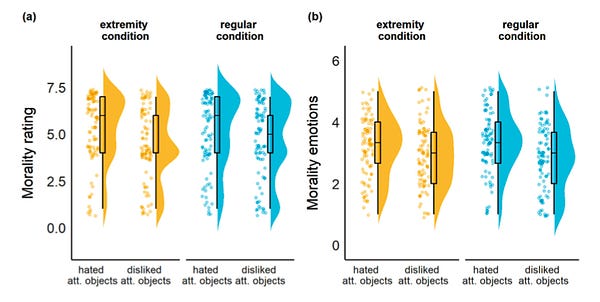

In line with the intensity hypothesis, people consistently reported more negativity towards the things they hated compared to the things they disliked but felt similarly negative towards the things they extremely disliked.

In line with the morality hypotheses, people also rated things they said they hated as more connected to their moral beliefs and emotions than the things they disliked. Indeed, this was true even when we compared hate to extreme dislike or statistically adjusted for the the intensity of their dislike.

In the fourth study, we found that the language used on prominent hate websites contained more words related to morality (but not negative emotions) compared to complaint forums.

Our studies provide evidence that morality differentiates hate from dislike in the minds of many people. Morality seems to be a critical ingredient in hate—and might be the reason people feel justified in harming others when hate spills over into real world conflict.

New papers and Podcasts

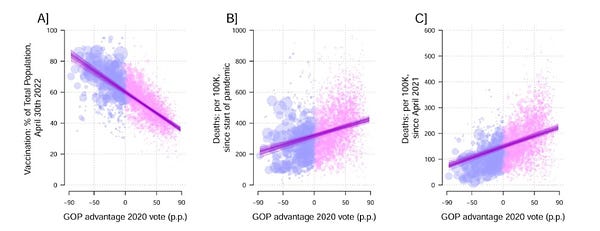

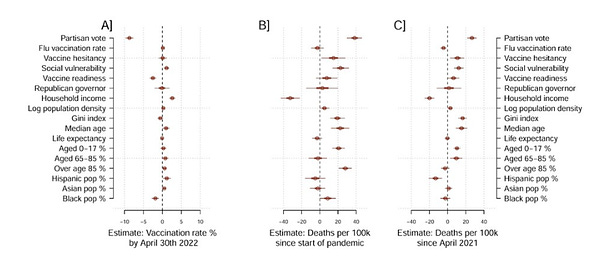

This month, we have a new pre-print from Jay, Clara Pretus, Steve Rathje, Philip Pärnamets, Madalina Vlasceanu and Eric D. Knowles on one of the signature features of the American response to the COVID-19 pandemic—political polarization. Our review of the evidence finds that Republicans were substantially less likely than Democrats to engage in physical distancing, wear masks and get vaccinated against the disease.

In fact, partisanship is the *single biggest predictor* of vaccination rates across the United States. It is more significant that race, education, socioeconomic status, or even pre-existing vaccinate hesitancy!

As a tragic consequence, these partisan disparities are linked to a significantly higher death rate in Republican-leaning areas of the country—and this partisan gap in mortality increased over time as the pandemic raged on.

Read the pre-print here to learn more about the effects of partisanship on the COVID-19 response as well as some important lessons learnt.

Can moral cognition be tuned by other factors beyond emotional intuition or deliberative reasoning? In our new chapter, Jay, Dominic Packer, Jennifer L. Ray, Claire Robertson and Nick Ungson outlined a process of “moral tuning”, where social contexts, especially social identities allow people to flexibly tune their cognitive reactions to moral contexts. They argued that social identities can alter moral cognition by influencing a person’s preferences and goals, shaping their expectations for others’ behavior, and affecting what outcomes matters to them. This suggests a powerful way to shift moral judgments and decisions—by changing identities and norms, rather than hearts and minds.

You can read the pre-print here:

Public outreach and Videos

While fandom culture for pop stars and sports seemingly has nothing to do with politics, is fandom making our politics even more toxic? It’s time to dive deeper into the social psychology of fans. Listen to this recent episode of Freaknomics where Jay explains how “being a fan” can shape our decisions and behavior.

In our individualistic society, are we still longing to unite as a group to solve problems and work towards common goals? Check out this episode of Aspen Ideas podcast where Science writer, Annie Murphy Paul; The New Yorker writer, Charles Duhigg and Jay discussed this matter.

Kim Doell, Madalina Vlasceanu and Jay gave a presentation about conducting and leading mega-studies. Recording now available on Youtube! Watch it here to learn some useful tips:

In the recent TED_Ed video they made, Jay and his co-author of the book The Power of Us, Dominic Packer explained the famous minimal groups studies, the roots of discrimination, and social identity theory. Watch it here to learn more about the science of intergroup bias.

Is polarization driven by the extreme? Listen to Jay explain to The Factual about group affiliations and political tribalism:

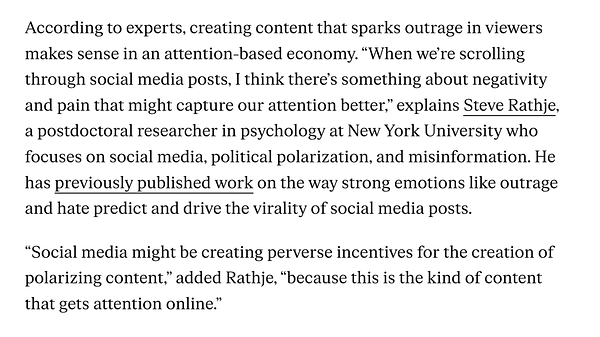

Last but not least, our post-doc Steve Rathje, talked about why disgusting recipes go viral on TikTok with Jessica Lucas for her article in The Verge. Read here if you are interested.

Announcement and Photos of the month

Former lab member, William J. Brady (and Nour Kteily) at Northwestern University is looking for a postdoc to work on their joint projects on collective behavior and intergroup conflict in the digital age. Check out more details here if you are interested in applying.

Earlier this month, Jay spoke at The AAMC Annual Meeting in Nashville on how to build healthy & effective groups and organizations. Here is a summary if you missed the event.

On Nov. 6th, 2022 New York City Marathon took place and a huge congratulations to two of our lab members, Jesper and Lina, who completed the 26.2-mile race through all five boroughs of New York City!

Jesper and Lina before the race

Jesper with his medal after the race

Lina and lab members at the finishing line

Finally, here are some belated tips on how to deal with friends’ and family’s political opinions that you disagree with at Thanksgiving dinner! Save it for the next Thanksgiving, or any upcoming reunion dinners in the Christmas season:

In case you missed last month’s newsletter…

As always, if you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to the Lab Manager (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com) who writes our monthly newsletter. We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

That’s all, folks—thanks for reading and we’ll see you next month!

Ingrouping/outgrouping heuristics are a helluva drug.

A review of WWI literature and history will conclusively demonstrate that nationalist hatreds were a creation of the conflict and not its cause. Moral indignation in Germany at the unexpected intervention of Britain made them, rather than France, Enemy Number One in the eyes of Germans. Whereas very little anti-British sentiment existed in the German population in 1914, by the spring of 1915, formerly-pacifistic German poets were writing verses about their hatred of Britain. There's a hysterical Punch cartoon of a German family "having its morning hate." Then in May of that year, a u-boat sank the Lusitania, and the next day there were riots in British cities. Mind you, there were no German victims, but the mobs only attacked immigrants. Inchoate rage.

Your hypothesis has more than a little merit.