The connection between political polarization and public health

There's a surprising connection between our public health and how divided we are politically.

News coverage about politics often focuses on how partisan divisions affect our politics. But our new paper suggest that political polarization also poses significant health risks to individuals and society—by obstructing the implementation of legislation and policies aimed at keeping people healthy, by discouraging individual action to address health needs, such as getting a flu shot, and by boosting the spread of misinformation that can reduce trust in health professionals.

“Compared to other high-income countries, the United States has a disadvantage when it comes to the health of its citizens,” says Jay Van Bavel, a Professor of Psychology and the lead author of the new paper, in the latest issue of the journal Nature Medicine. “America’s growing political polarization is only exacerbating this shortcoming.”

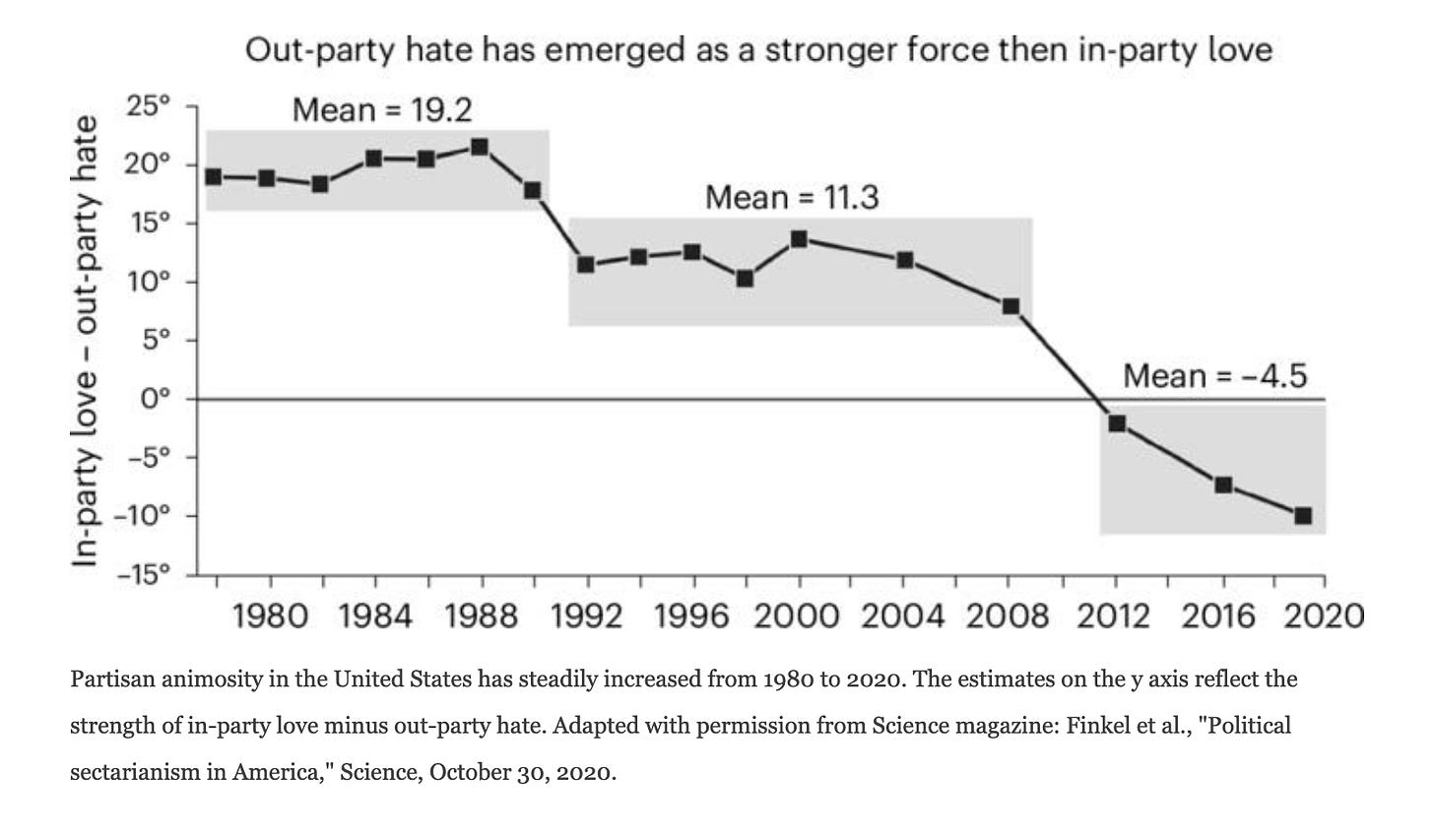

Over the past four decades, the paper’s authors note, partisan animosity has steadily increased in the US. By 2020, Americans were much more likely to say they “hate” the opposite party than they were to say they “love” their own party; by contrast, from 1980 through 2008, Americans were more likely to say they loved their own party than they were to say they hated the opposite party—though “party love” relative to “opposite party hate” has drawn closer virtually every year since 1980, becoming approximately even in 2012 and with “hate” surpassing “love” beginning in 2016.

Partisan animosity in the United States has steadily increased from 1980 to 2020. The estimates on the y axis reflect the strength of in-party love minus out-party hate. Adapted with permission from Science magazine: Finkel et al., 2020:

But despite the challenges of political polarization, our analysis, which considered more than 100 experimental papers and reviews, pointed to potential ways to both minimize its impact on Americans’ health and promote health-care practices.

“Division is a major problem and the one real solution is trust. Public health agencies need to work with trusted voices and leaders, being proactive at sharing information, engaging questions, and not writing off concerns as irrelevant,” says Kai Ruggeri, a Professor at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and one of the paper’s authors. “In a time when some people look less to doctors and more to prominent figures for information on decisions related to our health, the best steps involve engaging directly with those voices.”

The paper, which also included Eric Knowles, a Professor in NYU’s Department of Psychology, and Shana Kushner Gadarian, a Professor in Syracuse University’s Department of Political Science, considered Americans’ views of the opposite party, health-related behaviors during the coronavirus pandemic, and comparative data from other countries.

In their analysis and review, the paper also examined a range of health-care related studies, which found the following:

As individuals move further from the political center—in either direction—there is a deterioration in individual and public health, such as trust in medical expertise, participation in healthy behaviors, and preventive practices, ranging from healthy diets to vaccination. Notably, individuals who are more ideologically extreme than their state’s average voter have worse physical and mental health.

Polarization affects what health information people are willing to believe and shapes the relevant actions they are willing to take. This may mean disregarding accurate information or believing misinformation—depending on whether or not it comes from sources they are politically aligned with or disagree with.

Political leaders, inside and outside the US, may make public health worse by linking health behavior to partisan identity rather than medical needs or expert advice, thereby undercutting the role of expertise and ignoring approaches grounded in science, often leading to attacks on medical professionals and the healthcare system.

Republicans were less likely to enroll in marketplace insurance plans through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) than were Democrats after most of its provisions took effect a decade ago. These differences have been linked to excess sick days from work, higher healthcare premiums, and higher mortality rates.

As policy polarization at the state level has increased over time, so has the difference in lifespan and health across states—Americans who live in states with more progressive social policies, such as generous Medicaid coverage, higher taxes on cigarettes, more economic support (e.g., a higher minimum wage), and more firearm regulations live longer than their counterparts in states that embrace more conservative policies.

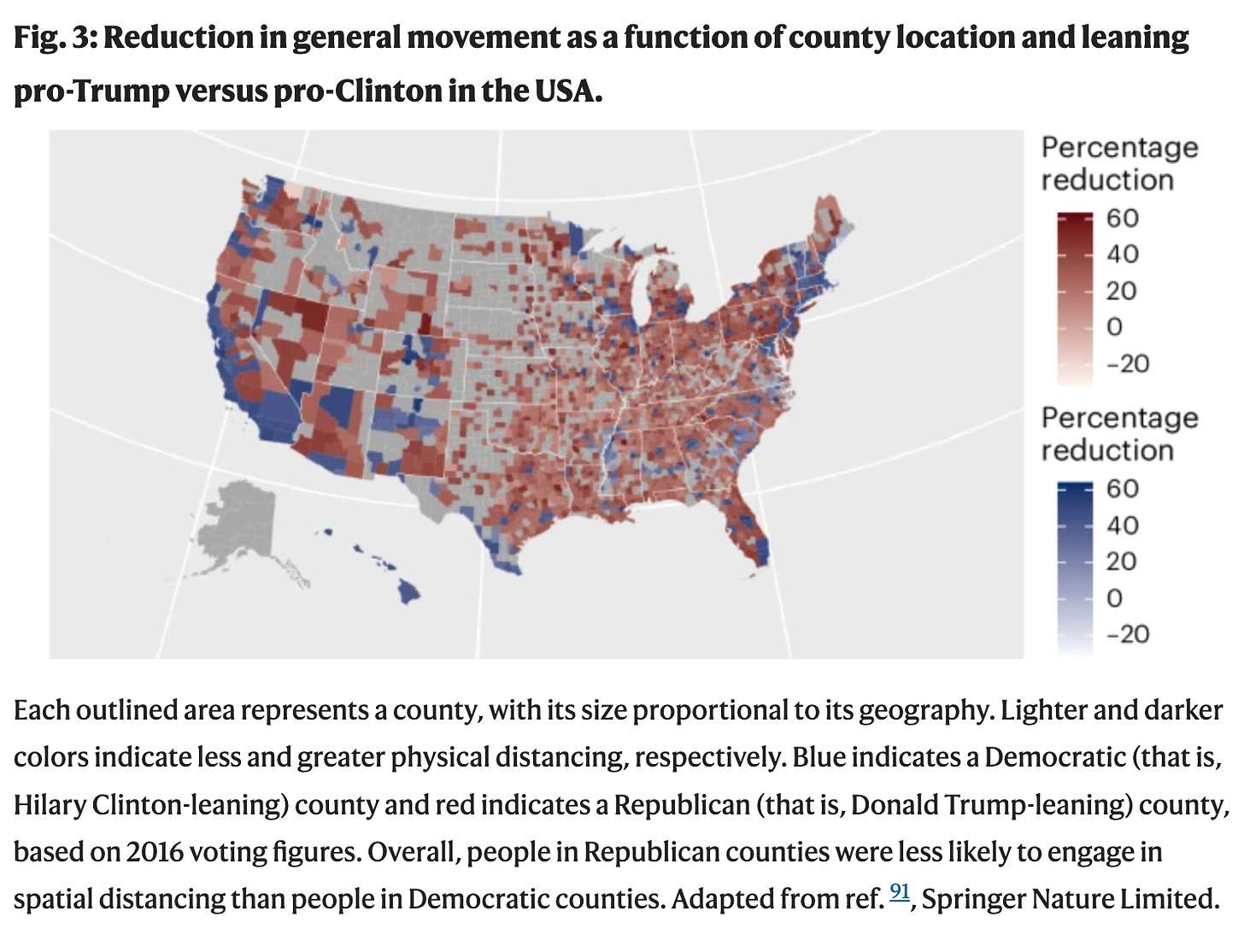

After the Trump administration and other Republican leaders expressed skepticism regarding COVID-19 prevention behaviors, partisan elites and news sources amplified this belief and polarized Republicans readily accepted it: large gaps in distancing and then vaccination rates between Republicans and Democrats widened during the pandemic, even as evidence mounted about the risks.

These differences were not limited to the US: a previous study of 23 European countries found that national levels of partisan polarization accounted for nearly 39% of the variation in vaccination levels.

Notably, another study of 67 countries found almost no correlation at all between left/right political ideology and support for public health recommendations, suggesting that polarization, rather than political ideology, was the greater risk factor to their citizens’ health.

“Compared to other high-income countries, the United States has a disadvantage when it comes to the health of its citizens. America’s growing political polarization is only exacerbating this shortcoming.”

The authors write that “although polarization is a risk factor for disease and mortality in a public health crisis, this outcome is not inevitable.” They point to a study comparing the US and Canada that suggests policy and leadership decisions can mitigate the potential harm from polarization. Although both nations were politically polarized at the onset of the pandemic, research found that political leaders in Canada took a different approach to those in the United States and also experienced a significantly lower level of illness and mortality.

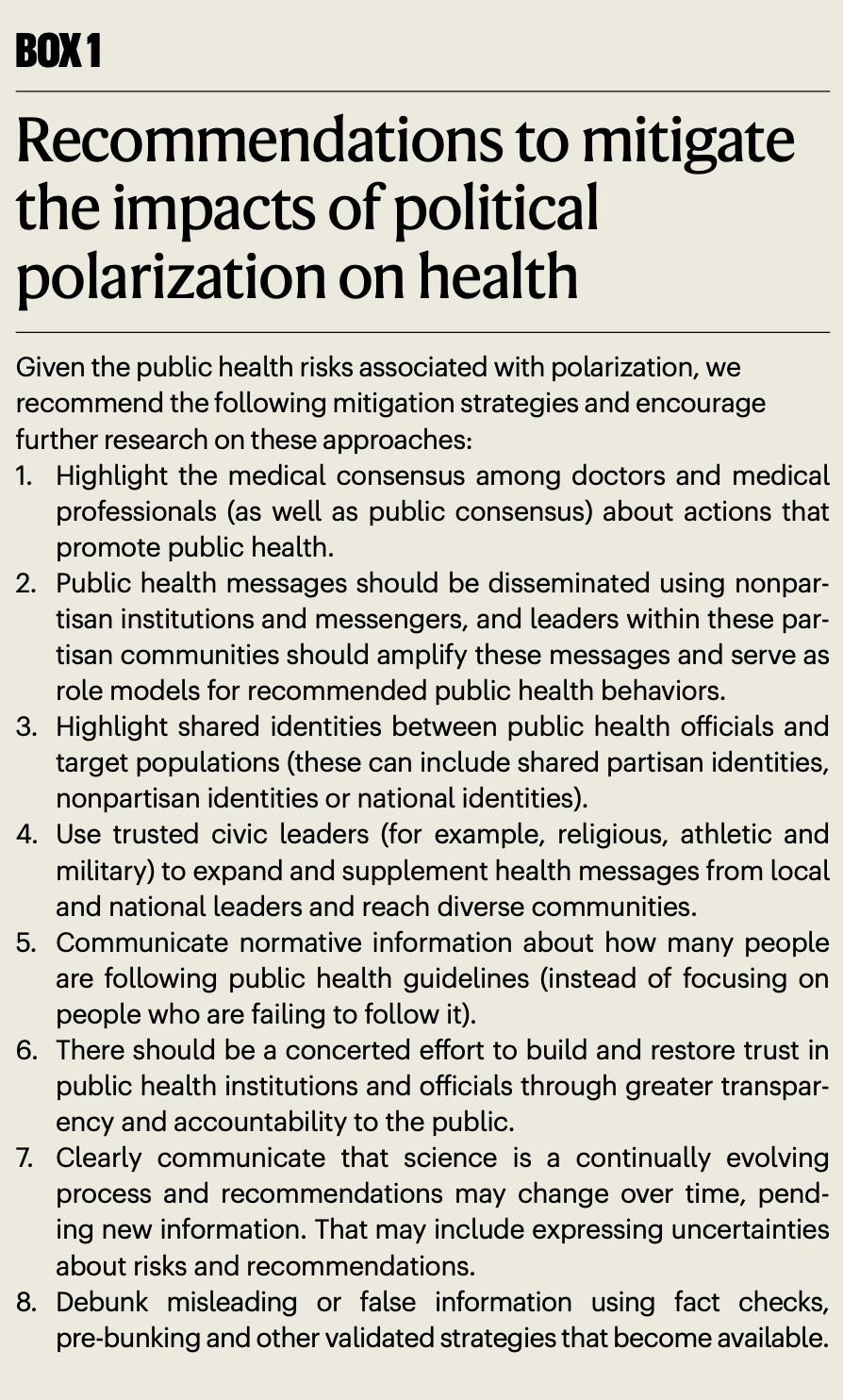

This and other studies point to specific approaches public officials and health-care professionals can take, which the Nature Medicine authors outline:

Highlight shared identities between public health officials and target populations—these can include shared partisan identities, nonpartisan identities, or national identities.

Communicate information about how many people are following public health guidelines—instead of focusing on people who are failing to follow it.

Use trusted civic leaders—such as religious, athletic, and military spokespersons—to expand and supplement health messages from local and national leaders and reach diverse communities.

Debunk misleading or false information using fact checks, pre-bunking, and other validated strategies

“Polarization is not only an American concern, but one that is increasing in many countries,” says Syracuse’s Shana Gadarian. “This means we should be investing more in understanding and diminishing its impact on public health by encouraging collaborations between medical professionals and social scientists.”

This month’s newsletter was originally a press release from NYU’s press office, written by James Devitt and with edits from jay Van Bavel. You can read the original here.

New Papers and Preprints

We just published a paper on intellectual humility, where we propose that intellectual humility functions on both the individual and collective level. The paper discusses how intellectual humility might be easier to reach as a collective, and potential barriers to building collective intellectual humility. You can read more here. This paper included Philip Parnamets, Aleksandra Cichocka, Jay Van Bavel, and several other collaborators.

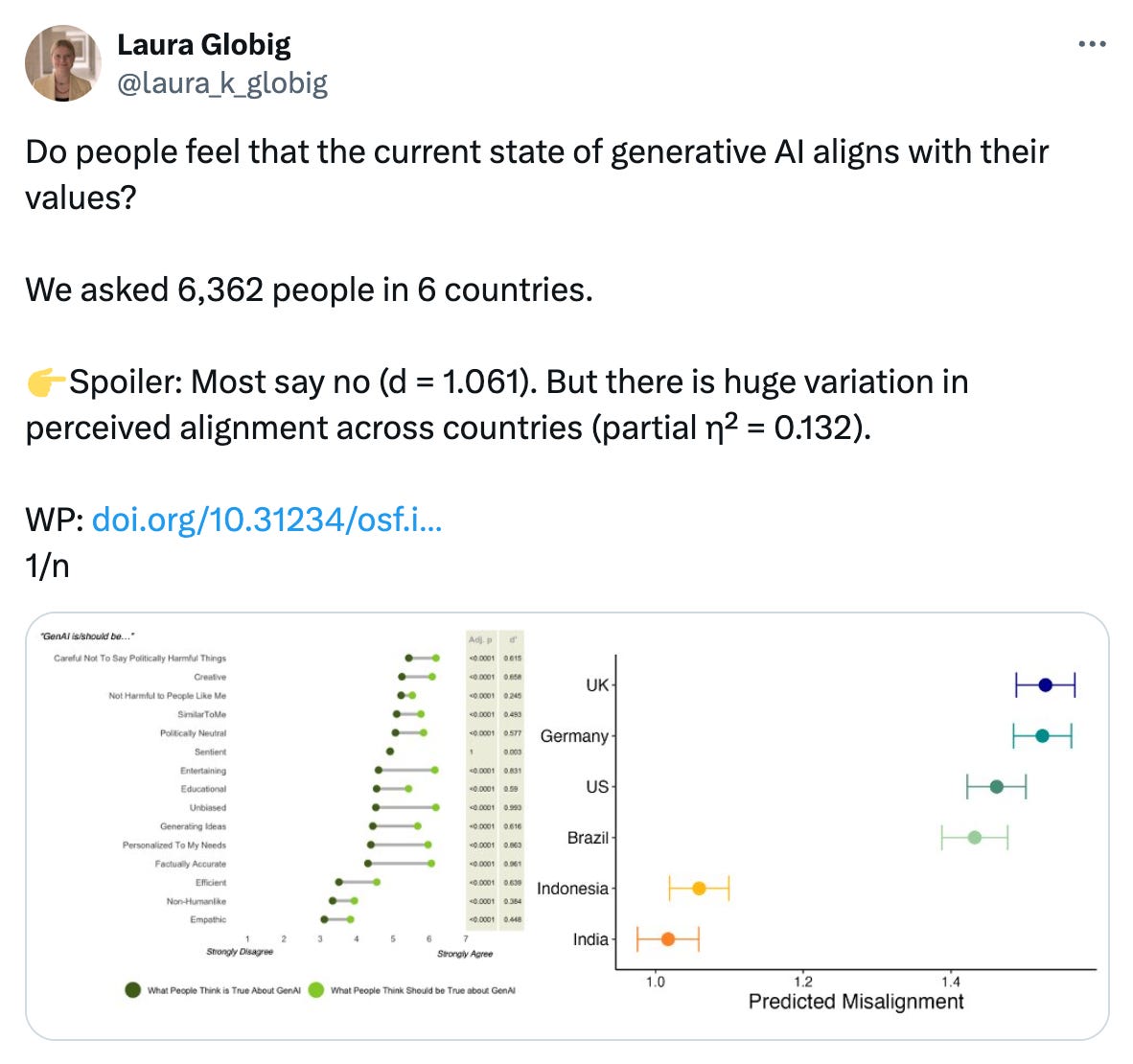

We recently published a preprint on people’s perceived alignment with generative AI in 6 different countries. While people generally feel that generative AI does not align with their values, alignment varies greatly across countries. People in Eastern countries (such as India and Indonesia) are far more trusting and optimistic about genAI compared to people in Western countries, despite many genAI technologies being developed in the West. Read more in the preprint here! This work was led by Laura Globig, Rachel Xu, Steve Rathje, and Jay Van Bavel.

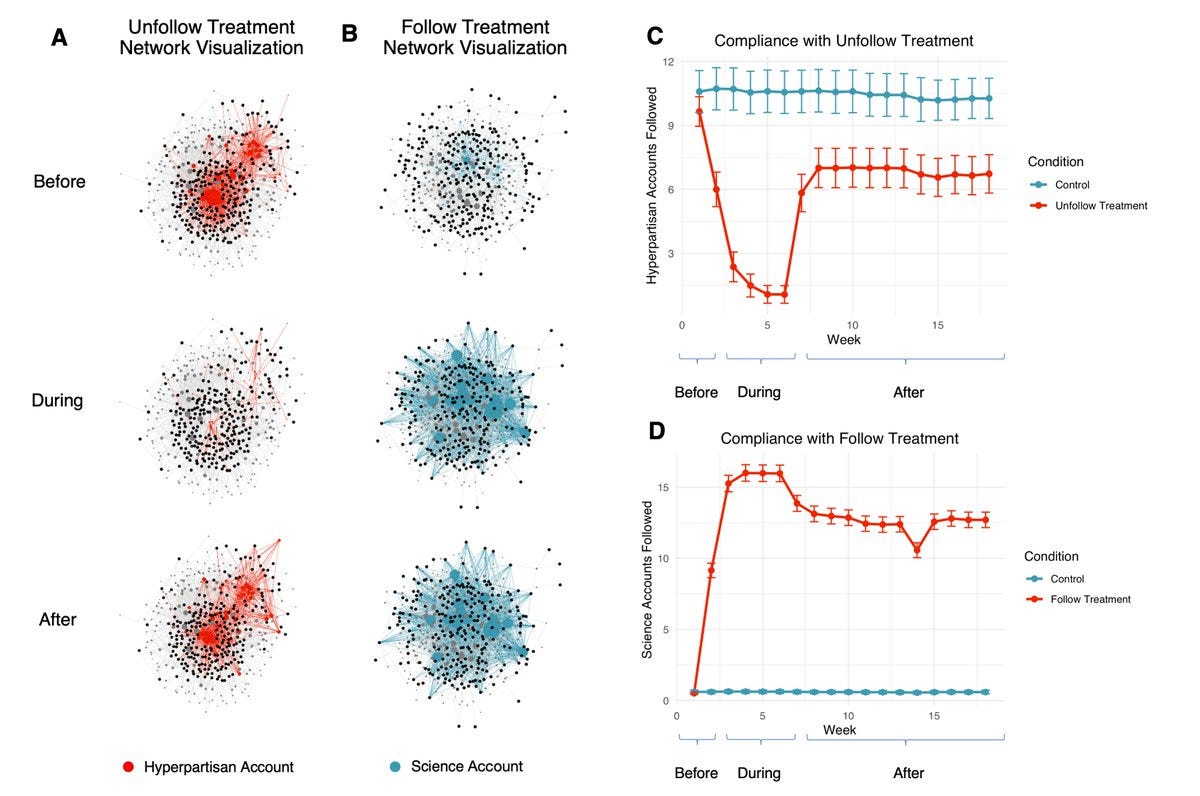

The preprint for our Twitter field study also came out recently. Over two digital field experiments, we find that unfollowing hyperpartisan influencers reduced partisan animosity, increased satisfaction with Twitter, and led people to share higher quality news. Read more in the preprint here. This paper was led by Steve Rathje, Sander van der Linden, Clara Pretus, James He, Trisha Harjani, Jon Roozenbeek, Kurt Gray, and Jay Van Bavel.

Postdoc Tobia Spampatti recently published a paper on how partisanship affects receptiveness to climate change information. Conservatives were worse at recognizing false information that aimed to delay climate action, and were more likely to misidentify true climate change information as false after being exposed to disinformation. You can read the entire paper in the Harvard Misinformation Review here.

We also published a review paper on how social media distorts how people perceive social norms. Social norms online tend to be more extreme than norms offline, which can create false perceptions of those norms, also known as pluralistic ignorance. You can read the entire paper here. This paper was led by Claire Robertson, Kareena del Rosario, and Jay Van Bavel.

A/V Spotlight

The NYU Social Psychology department recently hosted an academic job panel where faculty members (including Jay!) answered questions from PhD students and post-docs. If you want to hear the discussion, you can check it out on our YouTube channel. Huge thanks to lab members Laura Globig and Kareena del Rosario for organizing the event!

News and Announcements

Jay was recently interviewed by PBS News Hour, where he talked about our lab’s work on how a minority of social media users create a distorted reality on social media. Listen to the full clip here!

Jay was also featured on the Culture Matters podcast, where he discussed the science of social identities, and how we can use it to build healthy organizations and societies. Listen to the entire episode here!

Jay was interviewed by News Medical, where he talked about our recent review on political polarization and health. You can read the entire news story here.

If you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to our Lab Manager Sarah (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com) who puts together our monthly newsletter. We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

And in case you missed it, here’s our last newsletter:

That’s all for this week, folks - take care, and we’ll see you next month!