Individual-Level Solutions Can Support System-Level Change

Our new paper on behavioral interventions and social identity for positive spillover in tackling societal challenges and other news

How can we solve big problems we face as a society, such as climate change, poverty, or the COVID-19 pandemic? A recent article argued that solutions targeted at the level of the individual not only are insufficient but actually undermine much-needed system-level solutions. We published a response to their article, where we argue that this may not necessarily be the case and that individual-level solutions may support system-level change—especially if they are internalized as part of one’s social identity.

We firmly agree that change is needed at the system level to solve society’s most pressing problems. As Chater and Loewenstein put it in their recent article, we need solutions that “change the rules of the game” as opposed to “make subtle adjustments to help fallible individuals play the game better”. Consider the issue of climate change. Effective solutions likely involve significant regulation and policy changes, such as carbon taxes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Encouraging individuals to reduce their “carbon footprint” by introducing carbon footprint calculators will likely have a small impact in comparison.

But do individual-level solutions such as carbon footprint calculators take away from system-level solutions, for example, by reducing public support for system-level solutions? Or can they add to them, for example, by increasing support for system-level solutions? We think the answer may be the latter under the right circumstances. Specifically, we argue that individual behavioral interventions that harness people’s social identities may be particularly beneficial for achieving system-level change.

When an intervention aimed to change one behavior or attitude also changes another behavior or attitude, the intervention is said to have a “spillover effect”. Positive spillover occurs, for example, when an intervention to increase recycling also increases support for wind power. Negative spillover occurs when the intervention to increase recycling reduces support for wind power. Which of these two—positive or negative spillover—is more likely to occur?

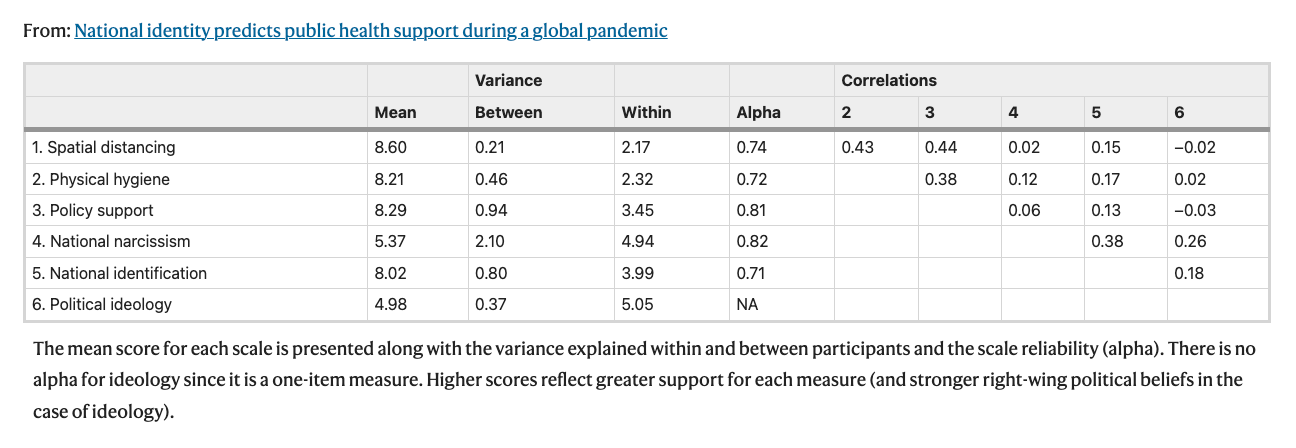

Prior research on spillover effects paints a complex picture: while some studies have provided evidence for negative spillover, many others provide evidence for positive spillover effects (e.g., Truelove et al., 2014). For instance, in a study of 49,968 people in 67 countries during the early stages of COVID-19, we found that support for individual behavioral change (e.g., spatial distancing and personal hygiene) was strongly correlated with support for system level change (e.g., policy support; rs = .44 and .38, respectively).

Part of the explanation for the mixed findings of spillover in the literature could lie in the choice of outcome measure. For instance, a meta-analysis of interventions to promote pro-environmental behavior found an overall positive spillover effect on behavioral intentions, a small negative effect on actual behavior, and no effect on policy support (Maki et al., 2019). But the direction and strength of spillover effects also varied across interventions, suggesting that there may be ways to increase positive spillover by using specific types of interventions or targeting specific types of behaviors or processes.

We believe social identity may be key to generating positive rather than negative spillover. In one study, participants who reflected on their pro-environmental behaviors in connection to their values or identity increased their support for a carbon tax (Sparkman et al., 2021). Similarly, people in our COVID-19 study who strongly identified with their country were more likely to support both individual and system-level policies (Van Bavel et al., 2022). This suggests that people who cared more about protecting their social group/country were most likely to act to reduce the spread of COVID-19 at all possible levels. This is precisely the type of change that will be necessary for addressing other massive societal problems, like climate change.

In our view, when a decision or behavior is based on a social role or identity (such as the identity of an environmentalist) or when an initial decision or behavior is attributed internally (for example, to one’s identity as an environmentalist), positive spillover may be more likely to occur (Truelove et al., 2014). This provides a powerful theoretical framework that combines an understanding of individual and collective psychology—which will be critical for mobilizing large scale change.

System-level change takes time and—at least in democratic societies—requires public support. Individual-level solutions could help mitigate social problems before system-level change is in place, could generate support among leaders and key stakeholders, and help generate necessary public support for system-level reform. Therefore, we should find ways to reduce the tradeoff between these levels of analysis. Considering social identity as key to generating positive spillover effects may help make sense of existing literature and provide testable predictions for future investigations.

Conferences and Outreach

On April 27th, Jay participated in the 16th Annual Psychology Day at the United Nations as a speaker. He presented on the power of social identities and morality to shape the mind, brain, and behavior.

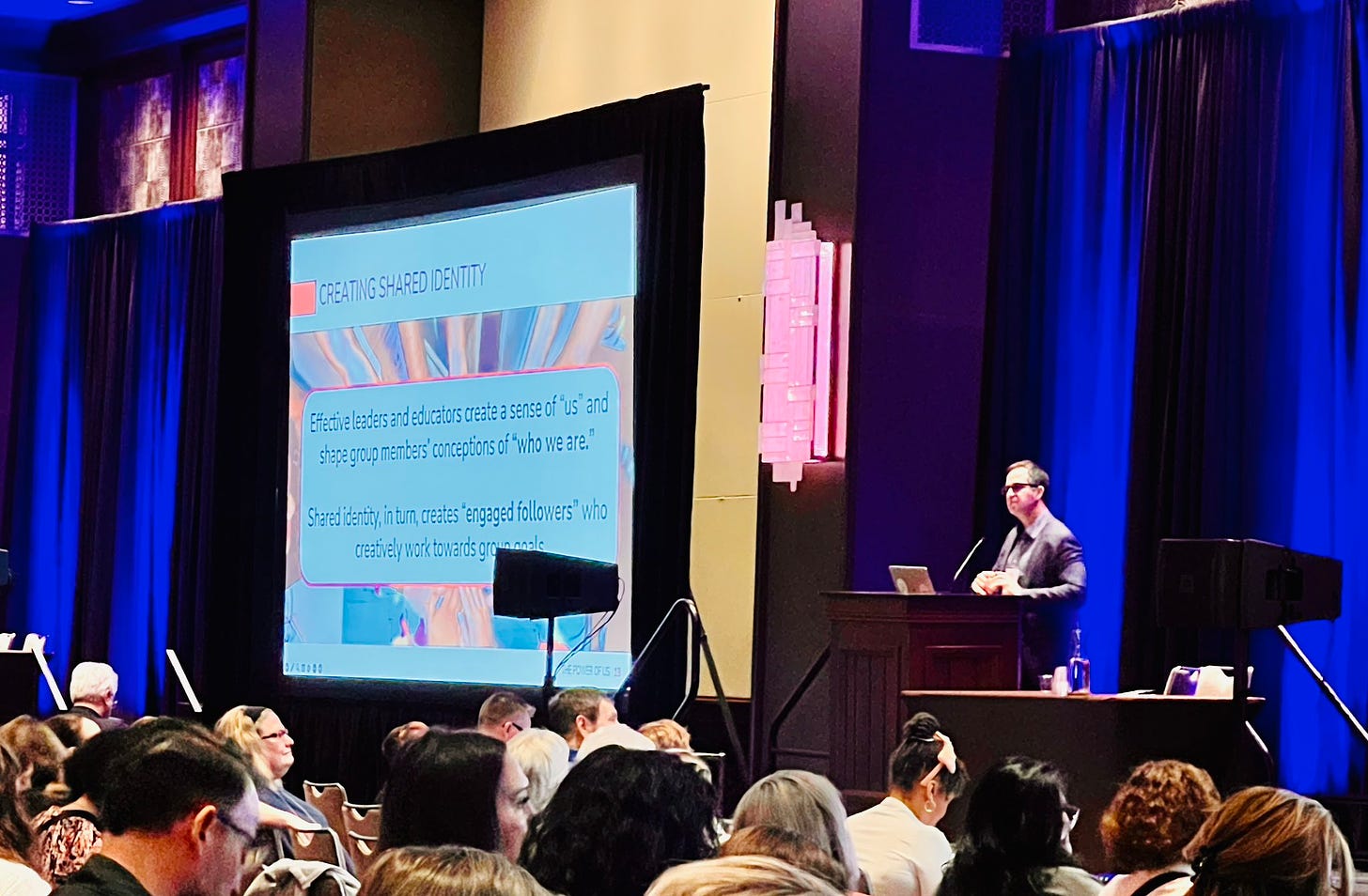

Jay also was the keynote speaker at Learning and the Brain Conference, sharing: The Power of Us: Harnessing Our Shared Identities to Improve Performance, Increase Cooperation, and Promote Social Harmony.

Videos

Last month, Claire Robertson, Nicolas Pröllochs, Kaoru Schwarzenegger, Philip Pärnamets, Jay and Stefan Feuerriegel analyzed the impact of negative and emotional words on online news consumption using a dataset of viral news stories in their new paper published in Nature Human Behaviour. Here is a short TikTok video Claire made with Steve Rathje discussing this paper. Check it out!

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

If you are in interested in threats to democracy, we also encourage you to watch this short documentary that Jay, Dominic Packer, Yvonne Phan and colleagues made on Protecting Democracy in a Time of Extreme Polarization. Watch the full video here or read the automated recap of the video here.

In recent lab meetings, Jay gave a series of presentations sharing the lessons he learned in graduate school. He outlines the mistakes he made in school and how students can avoid them. He also gives tips on how to invest time and maximize success in graduate school.

Part 1 and 2 of this three parts series focused on how to take care of yourself, how to build the big picture for your research career and how to develop the the skills you need during graduate school to launch a successful career in academia. Recordings for part 1 and part 2 are now available on Youtube.

As always, if you have any photos, news, or research you’d like to have included in this newsletter, please reach out to the Lab Manager (nyu.vanbavel.lab@gmail.com) who writes our monthly newsletter. We encourage former lab members and collaborators to share exciting career updates or job opportunities—we’d love to hear what you’re up to and help sustain a flourishing lab community. Please also drop comments below about anything you like about the newsletter or would like us to add.

That’s all, folks—thanks for reading and we’ll see you next month!